Antarctica: Where Emperors Rule the land

A landscape of extremes inhabited by whales, penguins, and icebergs, Antarctica has a magnetism like nowhere else. Jamie Lafferty reports from the frozen continent.

This is a feature from Issue 15 of Charitable Traveller.

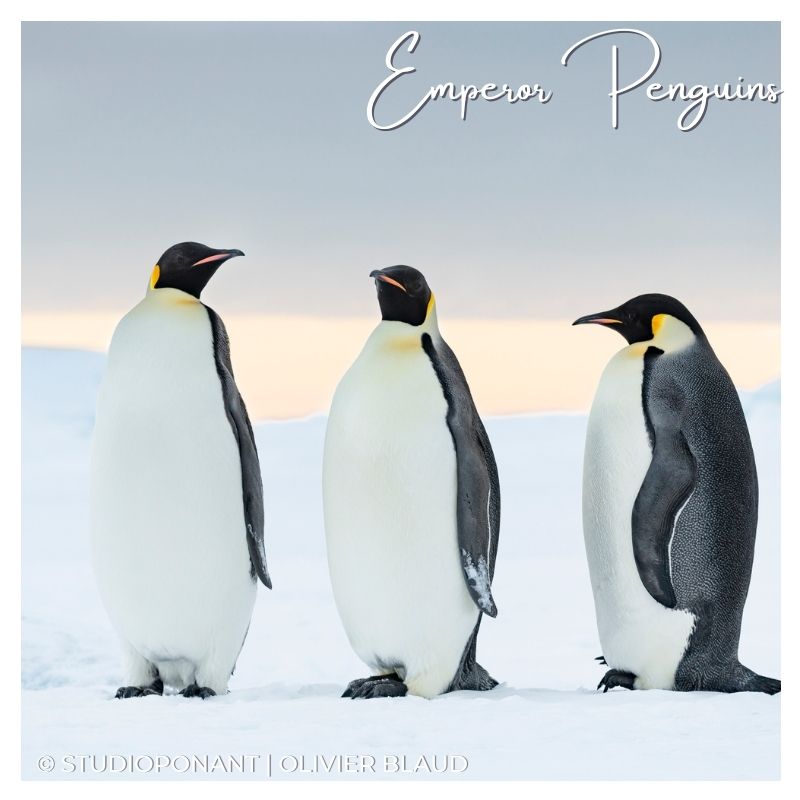

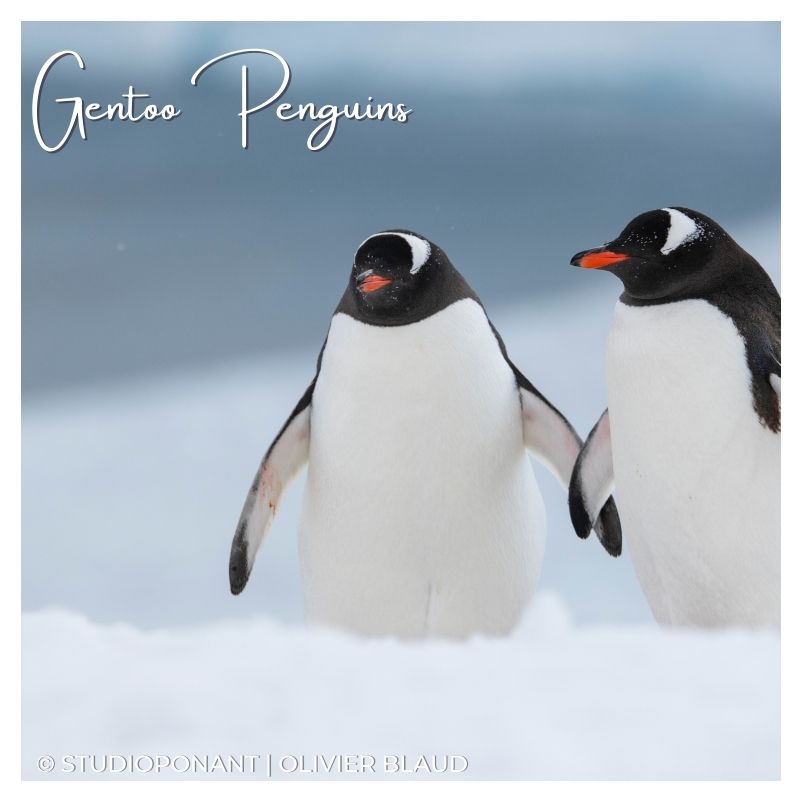

Adélie and emperor penguins are two of the world’s 18 penguin species, but they are the only two that nest exclusively in Antarctica. Visitors come to the icy continent for all sorts of things – the abundant whales, the impossible landscapes, the ludicrous history – but whether they are willing to admit it or not, penguins are almost always the most beloved prize.

I have never tried to resist the daft calls of the penguins. In 2022 I was able to return to Antarctica on writing and photography assignments on three occasions. On each, I saw penguins in such numbers and confusion that it was hard to document with my camera, let alone my pen. On South Georgia the mighty kings covered the island in their hundreds of thousands, occasionally interspersed with gregarious gentoos.

On the Falkland Islands, Magellanic penguins wandered newly landmine-free beaches just outside of the town of Stanley. Down on the Antarctic Peninsula, chinstrap penguins, with their black tongues and ugly calls, looked like little goths next to more colourful birds. The emperors were out of range though. To access their frozen territories requires dedication (and money) that keeps them out of most itineraries.

Exploring the ice

So popular has tourism become in Antarctica that the Peninsula is now close to capacity for cruise ships. Each must abide by strict rules defined by the Antarctic Treaty and those laid out by the International Antarctic Association of Tour Operators (IAATO), but nonetheless, with an estimated 100,000 tourists in the 2022/23 season, landing sites are being booked months in advance, and no ship is likely to sail without seeing others around the icy coasts.

However, as the industry expands and newer, greener, tougher ships are launched, so the continent opens up a little more. Currently standing above all other options is Ponant’s new hybrid-fuelled Le Commandant Charcot, and it has emperors within its range.

While virtually all polar ships have reinforced hulls, this 135-berth ship is the only official icebreaker currently carrying passengers. Put simply, this allows it to reach places no other company currently can. The Marseille-based company have not been shy in its deployment. In January 2023 I boarded Le Commandant Charcot for its first transcontinental cruise from Ushuaia, Argentina, all the way along the vast Antarctic coast, to Lyttleton, New Zealand. This was the port from which Cherry-Garrard, led by Captain Scott on his doomed mission to the South Pole, set sail in 1910. If their mission was defined by hardship, ours could hardly have been more comfortable. On board there are features so decadent as to seem inappropriate in the environment: a cigar lounge, a spa, a personal trainer in the gym, a fine-dining restaurant with a menu from Alain Ducasse, limitless champagne available from breakfast – and plenty of passengers willing to take

up that offer.

Some of these elements definitely feel more like a cruise than an expedition, but despite all that tinsel, what really matters are the decisions being made on the bridge by Captain Stanislas Devorsine. He’d been captain of a French Antarctic

icebreaker for a decade before joining Ponant. The chance to take charge of this new vessel was irresistible. “This ship is really amazing,” he tells me in his office one evening after a long day of bumping and crushing our way through pack ice. “There are many things I think she cannot do, but she does. For me it allows maximum flexibility.”

Also on board is a helicopter, which I initially feared might be used for gratuitous sight-seeing flights. In fact, it’s used exclusively to scout out ice conditions ahead. The ship may be reinforced, but when pieces of tabular ice are not only longer but taller than her, the captain has to give them a wide berth. Between the pilots, the captain, and weather so favourable I could spend afternoons reading on my balcony, we push on to some extraordinary latitudes, leaving the crowded Antarctic Peninsula far behind.

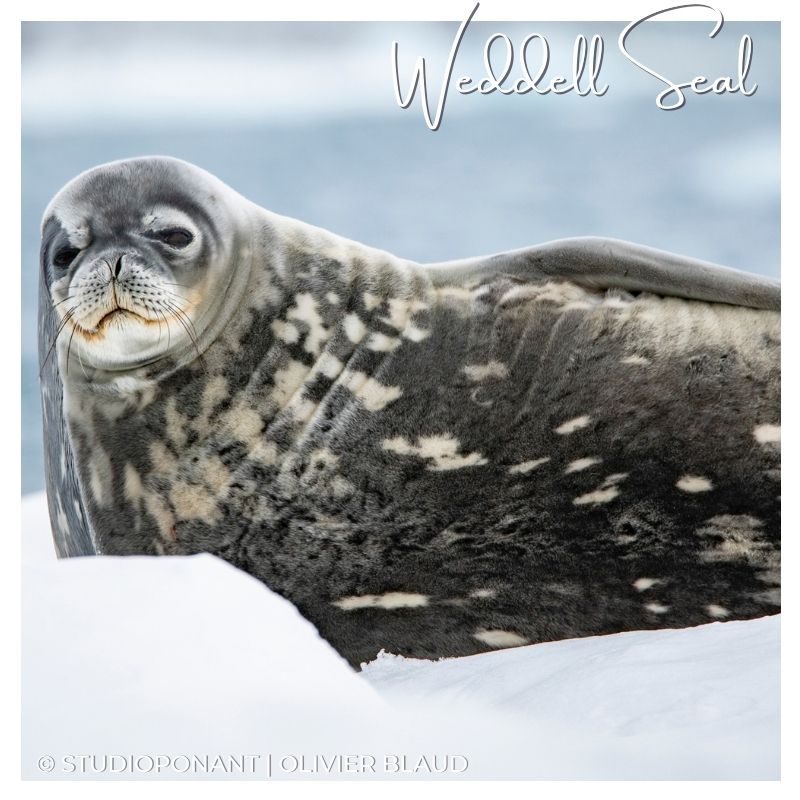

IAATO provides ships with briefings on what to expect and how to behave at landing sites, but on places like Sims Island – a dramatic, Mordorian black rock – they have no information. On the Brownson Islands, deep into the Amundsen Sea, charts are useless – many of the islands haven’t even been named. No tourist ship had ever visited before, nor seen any of the 6,000 emperor penguins thought to nest here in winter. The Antarctic skuas and hardy little Adélie penguins living there in the austral summer were unlikely to have ever seen humans before, either. As I slide out of the motorised Zodiac and on to the unnamed shore, expedition leader Florence Kuyper offers me a firm sailors’ grip. I see a look of delight in her face and realise she is seeing the same on mine, too. “This,” she says, casting an arm across the bay in front of us, “is the stuff.”

Get in touch with our expert travel agents today to plan your perfect Antarctic Expedition, and donate 5% of the price to the charity of your choice for FREE!

This is a feature from Issue 15 of Charitable Traveller.

by net effect

by net effect