This is a feature from Issue 17 of Charitable Traveller.

The darkness of Tsumago wraps itself around you like a cloak. After dinner, we were urged to go for a stroll but as our inn sits on the edge of the village, after ducking out of the sliding door and past the welcoming glow of its entrance lamp, we have to

feel our way down the path. The air is clear and cool and the sound of rushing water fills our ears before our eyes adjust.

Above, is a map of stars, like diamanté studs in black velvet. Shrouded in darkness but looming large is Carp Rock, a giant boulder and a landmark to weary travellers for centuries.

Our starlit reverie is interrupted when we come across another western couple, like us stumbling in the dark and dressed in an awkward combination of yukata robes and trainers.

The man lets out a loud fart which carries spectacularly on the still night. We pretend not to have heard as we greet them good evening, smiling a little too wide. I wonder if Tsumago evenings are always full of tired tourists, preemptively letting off wind before they settle down for the night, separated from each other by paper-thin walls.

Tsumago is a town on the Nakasendo Way, an ancient post road connecting Tokyo and Kyoto. Meaning “central mountain route”, it winds its way through Japan’s Central Alps for over 300 miles, dotted with 69 post towns. We have come to it from Tokyo, and the contrast is startling.

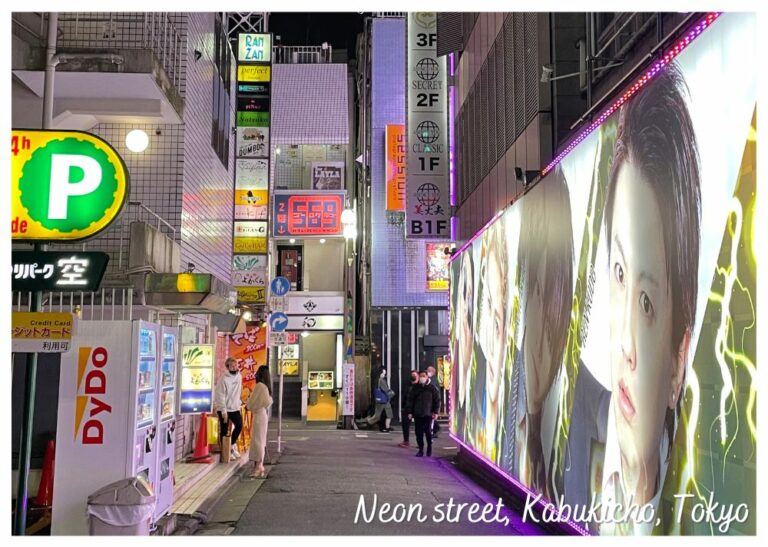

This time last night we were emerging out of Shinjuku station, dazzled by the intense glare of myriad lights, screens and signs. Watched over by a gigantic 3D cat in a police hat, pictured on a giant screen on top of a skyscraper, we entered the seedy red light district Kabukichō under a fluorescent arch. We passed strip-lit convenience stores and fast food joints and less than salubrious bars and arcades which spilled flashing lights and music on to the street. Godzilla peered from the roof of Toha Cinema, raking the streets with his lizard glare.

We joined salarymen in crumpled suits, expelling the frustrations of corporate life at the batting cages. For a few hundred yen you stand in a netted arena as a machine fires baseballs at you to hit in quick succession.

Afterwards we hit Golden Gai, a handful of cramped alleyways crammed with hundreds of atmospheric bars, most so snug that they only fit five patrons at a time. The squat pre-war buildings are a rarity in Tokyo, giving the place a time-capsule appeal.

But as time capsules go, the Nakasendo trail trumps all. We travelled to a portion of it in the Kiso Valley, via a bullet train to Nagoya, before changing on to the Chuo Main Line, instantly feeling the change of pace as we chugged to Nakatsugawa on a local train. From here, a bus wound us up to Magome, past rice fields and quiet villages.

Magome is one of the Nakasendo’s most polished towns. From the bus stop, a single street climbs steadily up past lovingly restored wooden buildings. With their overhanging eaves and dark wood beams, they aren’t dissimilar to Swiss chalets. It’s late October and the air is fresh in the golden sunshine. Water gushes down a narrow stream that runs alongside the street, and at several points big rustic wooden wheels are placed to catch the torrent. The noren curtains hanging over doorways, printed with kanji characters, remind me I’m in Japan. Shops sell snacks, like steamed buns filled with sweet red bean paste, and souvenirs including chopsticks, clay cats, postcards and crockery.

The Nakasendo was established in the 1600s, when Japan was ruled from Edo – now Tokyo – by the Tokugawa Shogunate, a military government.

Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu established sankin kōtai, a system which required Japan’s feudal lords, called daimyo, to live in Edo for months each year, and leave their families there when they returned to check on their lands. This required a good transport network and the Nakasendo linked Edo to the imperial capital of Kyoto. It was also a way of keeping the daimyo in check – their travel expenses left them little capital for staging a rebellion. In its heyday, the Nakasendo was plied by daimyo, servants, messengers, traders, samurai, royalty and pilgrims.

The houses thin out as we leave Magome, passing a look-out point with the Alps stretching into the distance, before the path narrows

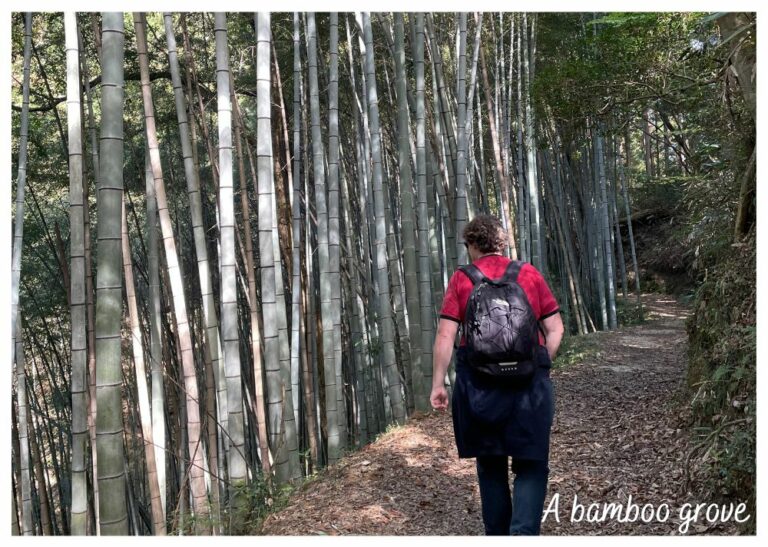

and enters forest. This stretch is popular because it’s just eight kilometres long, but we quickly lose the crowds, passing a grove of whispering bamboo before finding our first bell to warn off the black bears. Also dotted along the trail are mossy stones carved with small human figures. These are dosojin, a Shinto kami, or spirit, believed to protect travellers from evil spirits.

The road winds through a hamlet of wooden houses, fronted with neat potted plants. Bunches of red chillies dry in the sun and persimmon trees hang heavy with orange fruit. As we climb higher, the trees’ russet hues are more pronounced. We pass the entrance to a lonely Shinto shrine, its wooden torii gate peeking out among tall cedar trees. Shortly after this we cross the highest point and begin to descend, stopping at a teahouse.

Run by a friendly elderly man, it’s housed in an Edo-period building, with sliding doors into a dark room where we help ourselves to green tea and sour cherries for a donation. A sunken hearth is built into a wood platform, with an iron pot hanging above it, but it’s not chilly enough to light the fire. There’s a faded picture of Joanna Lumley on the wall, taken when she visited filming a documentary.

The last big attractions are the Odaki and Medaki waterfalls, which gush over boulders into clear sandy pools in the forest. From here, the fern-lined cobbled path winds down through the trees. More houses appear as we approach Tsumago, crossing a pale blue river. At the village’s entrance is a shrine offering bottles of sake for the kami. It’s already dusk, and the warm lights of square lanterns hang from the wooden houses. Tsumago is more rustic than Magome but still beautifully preserved. Bunches of pretty dried flowers hang from windows, along with teru teru bōzu, ghost-like dolls which are a talisman to bring good weather. Many of the trees are lovingly clipped into fanciful bonsai-style shapes.

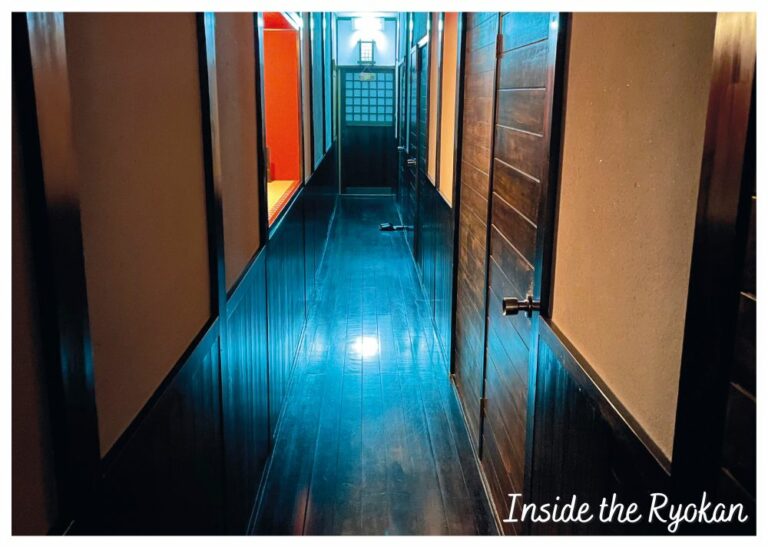

We are welcomed to Daikichi, a tiny ryokan (traditional inn) with sliding paper doors and tatami mat floors. We don’t have long to relax in our simple room before we’re summoned for dinner. Our host corrects my yukata, provided to wear for the evening. I’d hurriedly folded it right over left – usually reserved for dressing the dead, apparently, which explains her brief look of horror.

We sit opposite each other on zaisu, wooden legless chairs. Each of us has a low lacquer table which we slide our legs straight under. Dinner consists of cold soba noodles, sizzling stringy white mushrooms, trout, beef sashimi, crunchy crickets, a creamy liquid tofu, tempura vegetables and a steaming basket of red rice, with a

glass of sweet cherry wine. It’s a feast, but a Japanese one – so delicately balanced and not gluttonous.

After our night walk yields no place to grab a beer, we wander back. I shuffle down the polished wooden corridor, passing the other rooms with leather slippers lined outside, and lock myself in the communal bathroom. I shower first, as instructed, before slipping into the steaming ready-poured wooden bathtub. Afterwards, I sleep like the dead.

The next day brings bright sunshine and a breakfast of miso soup, fish, egg and green tea. It’s less than an hour’s walk to catch

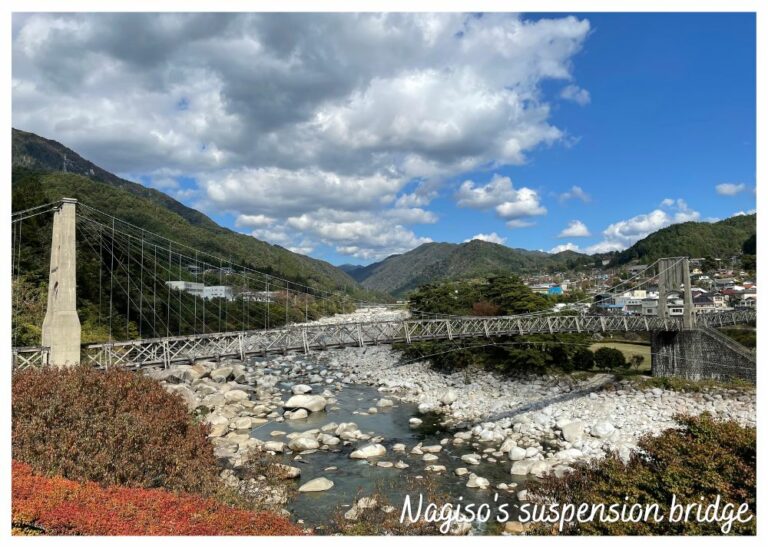

the train to Kyoto. The next town of Nagiso is more modern and sprawls along the wide Kiso River, which rushes over white boulders and is straddled by an impressive wooden suspension bridge. On the edge of town we pass a cluster of Jizo statues, stone figures dressed in tiny red bibs and wool hats – another protective deity for travellers, but Buddhist. We lunch in a charming café, with regular’s tabs hanging behind the bar and shelves of books lining the wooden walls. Cold beer and crunchy katsu curry mark an end to the walk.

Our journey ends in the imperial capital, and although Kyoto is no mega city like Tokyo, after the Kiso Valley it feels like one. As dusk falls, we join throngs of people crossing the Kamo River from modern Kyoto into Gion, the geisha district.

Ahead of us two girls in flower kimonos glide elegantly. The luxurious wooden ochaya, or tea houses, along Hanamikoji Street are bathed by lamp light but windowless, offering not even a tantalising glimpse of what goes on within. The darkness and silence of Tsumago

already feels like a dream, but I can imagine how those who walked the Nakasendo’s full length would have felt arriving here – sheer relief.

Get in touch with our team of expert travel agents to plan your perfect Japan holiday today! Remember – everytime you book a holiday with us you can donate 5% of your holiday price to the charity of your choice for FREE!

This is a feature from Issue 17 of Charitable Traveller.

Fundraising Futures Community Interest Company, Contingent Works, Broadway Buildings,

Elmfield Road, Bromley, Kent,

BR1 1LW. England

Putting our profit to work supporting the work of charitable causes

For the latest travel advice, including security, local laws and passports, visit the Foreign & Commonwealth Office website.

© 2024 All rights reserved

Made with

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELB | session | Associated with Amazon Web Services and created by Elastic Load Balancing, AWSELB cookie is used to manage sticky sessions across production servers. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |

| JSESSIONID | session | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __lc_cid | 2 years | This is an essential cookie for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __lc_cst | 2 years | This cookie is used for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __oauth_redirect_detector | past | This cookie is used to recognize the visitors using live chat at different times inorder to optimize the chat-box functionality. |

| aka_debug | session | Vimeo sets this cookie which is essential for the website to play video functionality. |

| player | 1 year | Vimeo uses this cookie to save the user's preferences when playing embedded videos from Vimeo. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 6 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_164521185_1 | 1 minute | This cookie is set by Google and is used to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| _hjid | 1 year | This is a Hotjar cookie that is set when the customer first lands on a page using the Hotjar script. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description available. |

| CONSENT | 16 years 3 months 16 days 17 hours 23 minutes | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. They register anonymous statistical data on for example how many times the video is displayed and what settings are used for playback.No sensitive data is collected unless you log in to your google account, in that case your choices are linked with your account, for example if you click “like” on a video. |

| iutk | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is used by Issuu analytic system. The cookies is used to gather information regarding visitor activity on Issuu products. |

| vuid | 2 years | Vimeo installs this cookie to collect tracking information by setting a unique ID to embed videos to the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Google DoubleClick IDE cookies are used to store information about how the user uses the website to present them with relevant ads and according to the user profile. |

| mc | 1 year 1 month | Quantserve sets the mc cookie to anonymously track user behaviour on the website. |

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |