The fisherman's Way Portugal

If you thought you knew southern Portugal, think again. Lynn Houghton heads away from the crowds to walk in the footsteps of the hardy fisherman who have worked its wild west coast for centuries.

This is a feature from Issue 10 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

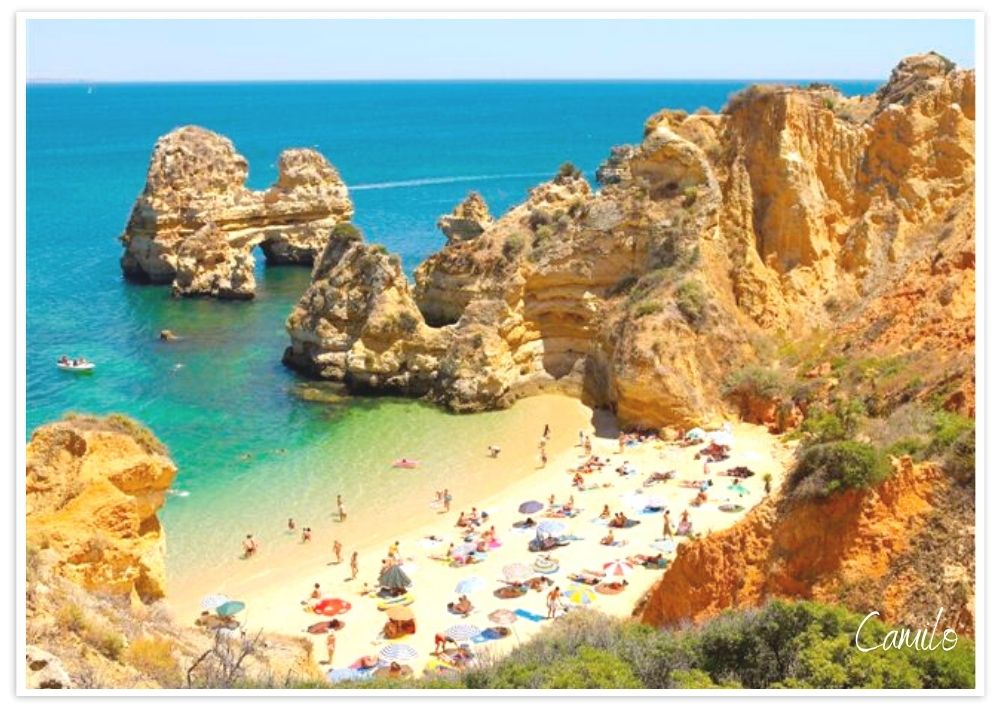

The craggy and windswept path that is the Fisherman’s Way begins in the tourist hub of Lagos, trailing up and down the edge of the dramatic red snd ochre cliffs that line this popular coast. Holiday makers have been visiting the sun-soaked Algarve resorts of Lagos, Albufeira, and Faro since the 1960s, to enjoy their golden sand beaches, calm waters, fresh seafood and sun-dappled skies. But, for those who to venture westwards, there is a less explored part of this region which has ample rewards too.

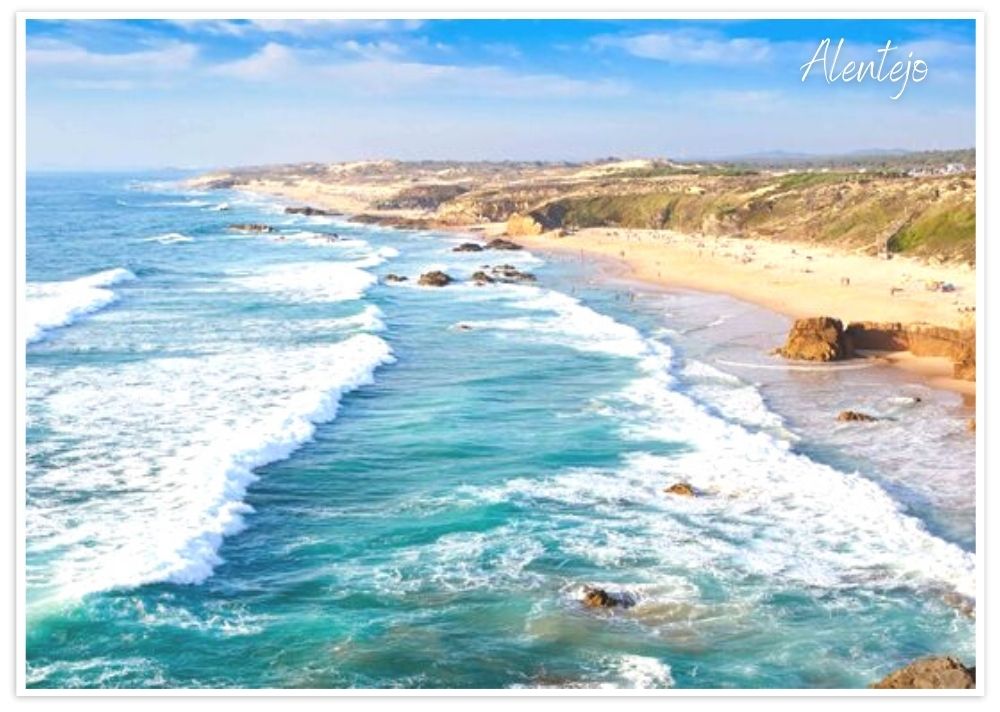

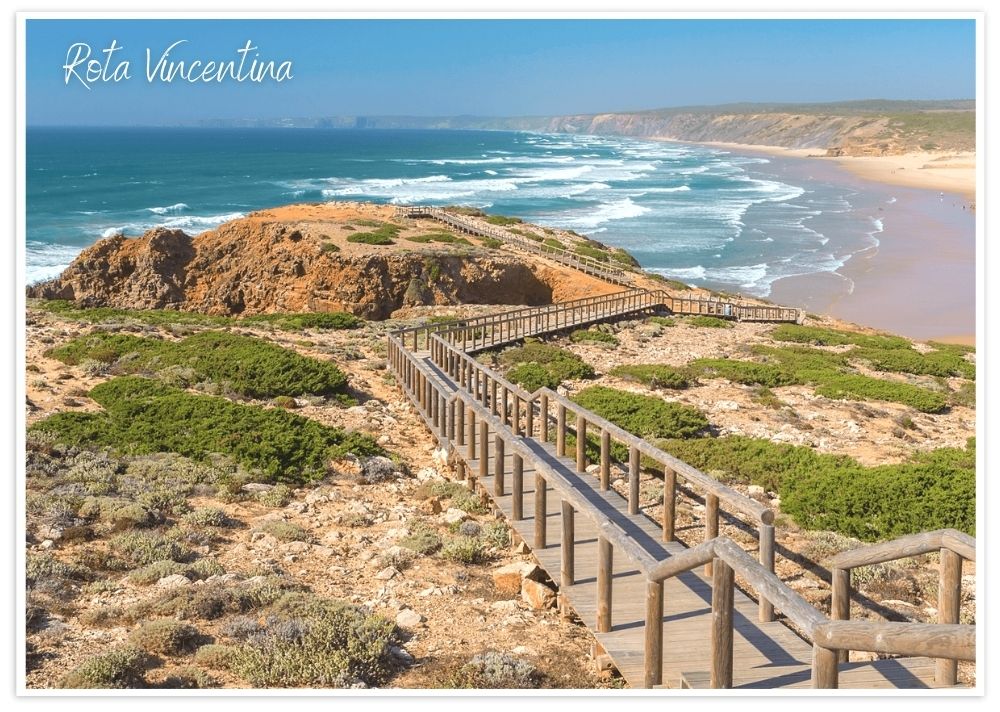

You can walk mile-upon mile of undeveloped, rugged, coastline into the western Algarve. Fisherman’s huts, rustic farms, and small villages are prevalent here rather than big resorts, and just off the the road you’ll see shepherds tending their goat herds . To walk the entire Fisherman’s Way, which is 143 miles long, takes between 11 and 13 days and will take you from Lagos, around the Algarve’s coast into the neighbouring region of Alentejo, ending on the golden dune-backed beach of Praia de Sao Torpes on the Atlantic coast.

Go West

I start in the white-washed fishing village of Burgau, 12km west of Lagos, but if you fancy exploring the rural inland area of the Algarve, there is an alternative Fisherman’s Way track that turns north rom Lagos to Odeceixe. It’s a clear day, perfect for walking, although I stumble a bit at the start because the shale path is tricky to negotiate. Luckily I have company from fellow hikers and volunteers, Ana, Diogo, and Riccardo, who are also tasked with refreshing the blue and green stripes painted onto various rocks that helpfully mark the way. The dramatic terrain along the path is at odds with the peaceful mood, battered as it has been by the forces of nature since it was formed. The delicate greywacke (a type of sandstone) cliffs have been pummelled and sliced by merciless wind and waves. But lying at the bottom of these cliffs are virtually empty golden sand beaches, where you can lie down and gaze upon the basalt outcrops just off-shore, home to large nesting birds like pelicans and storks.

After half an hour, our group reaches a flat area and we position ourselves on the cliff edge to watch the surfers off the Praia dos Rebolos below. After descending a particularly steep section of the trail, we stop to indulge in a seafood lunch typical of this region. O Laurenço in Salema serves up a mean arroz do timbani (rice stew with monkfish) and, afterwards, we have espressos and the obligatory pastry dessert, a pastel de nata, which is a flaky custard-filled tart.

The End of the World

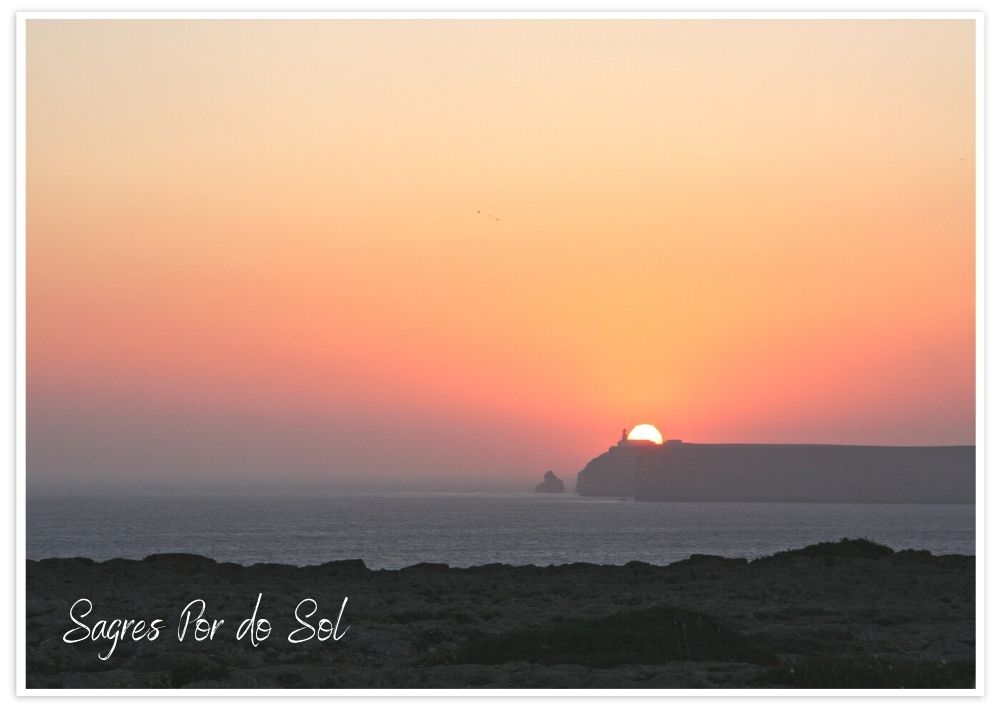

Hundreds of years ago, Sagres, the southwestern-most tip of Europe, was considered to be the end of the known world. The Greeks, and after them Romans, thought of it as a mystical place and an important destination for pilgrimages. The Arabs were also attracted to the area and invaded, dominating for over 500 years until 1250AD. They left behind salt pans, carob, and almond trees as well as unique chimneys, beautiful fountains and water features. In those days al-Andalus, as it was known, was dramatically cut off from the rest of Portugal by the Serra de Monchique mountain range. Today it still feels that way. The Sagres peninsula continues to draw pilgrims along with tourists and surfers.

The flat-topped promontory has been battered by the elements over millennia but it’s remarkable to see the abundance of plants that manage to grow here, notably the Phoenician Juniper and an indigenous white rock rose. Other endemic plants include Vincentin Germander, a fragrant shrub with tiny mauve flowers similar to lavender; Sagres Candytuft, with its frilly white petals; purple violets; a wild form of rocket which grows in the cracks of sun-warmed rocks; a magenta-hued sun rose and the hardy purple and yellow flowered goat’s thorn.

Sagres attracts a curious mix of people, with fishermen, farmers and surfers living cheek-by-jowl. Many flock here to see the historic fort, which sits on a staggeringly huge cliff overlooking the ocean. A few miles further north, another peninsula juts out to sea and provides the location of the Cabo São Vicente Lighthouse. On approach, the lighthouse is so close to the cliff’s edge it appears to be floating above the ocean. The views out to sea are similarly spellbinding.

And Relax...

I give my feet a rest and drive north from Sagres, entering the Parque Natural do Sudoeste Alentejano e Costa Vicentina, unique for being the largest coastal wilderness in continental Europe. As there is so little development here, it is also known for its excellent stargazing. Exploring the steep coast is certainly easier if you have somewhere luxurious to retreat to and Praia do Canal provides just that. Planning permission for the resort was in place before the park boundaries were decided so it’s a unique addition to an area mainly inhabited by farms and a few scattered villages.

Nevertheless, Praia do Canal prides itself on its sustainable ethos and blends into its natural background of grassy meadows and pine trees. Named after the nearest beach, though that is nearly an hour’s walk away, the 56 room resort is made up of slender, modern, box shaped buildings. Indoors are artistic renditions paying homage to the area: sculptures from tree roots, hand-carved wooden tables, wicker encrusted chandeliers and even olive trees growing out of the tables at the Azeitona Restaurant. The infinity pool nestles in a boxed-in garden next to the spa which has two treatment rooms, a hammam and an indoor pool. From the grounds are three trails that take guests on treks into the meadows around the resort. But most staying here go further afield, visiting nearby beaches and villages or taking horse rides. I join the chef on a shopping expedition to find goose barnacles (a local delicacy) for dinner. We end up in the tiny beach village of Arrifana, where red-roofed houses zig-zag down the steep coast to yet another perfect golden arc of sand. I promise myself I will return here, either to explore the clifftop on foot or paddleboard around the rock formations.

But, for now, lunch at the superb fish restaurant perched on the very edge of the town will do. O Paulo not only has astonishing ocean views but a menu that celebrates the fruits of the sea below. After sampling a gratin of scallops and shrimp, octopus salad, fish soup, and beautifully cooked razor clams, spider crab, oysters and lobster, we settle onto the balcony with a cold Sagres beer to watch the sun sink into the glittering ocean and pink-washed cliffs fade to black silhouettes.

This is a feature from Issue 10 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

by net effect

by net effect