Exploring Tokyo in a day and a half means Laura Gelder finds herself thrown between extremes, from robot toilets to ancient temples

This is a feature from Issue 7 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

My toilet seems to have its own mission control panel and in my jetlagged state it’s making me anxious. I’m trying to work out how to flush and helpfully the myriad buttons have English translations to explain their use, like: “Equipment to cleansing the buttocks with warm water.” Not really what I’m looking for, although apparently, “the angle of cleansing water coming in contact with the buttocks is adjustable.” Impressive. I give up and rise from the loo, at which point it promptly flushes automatically.

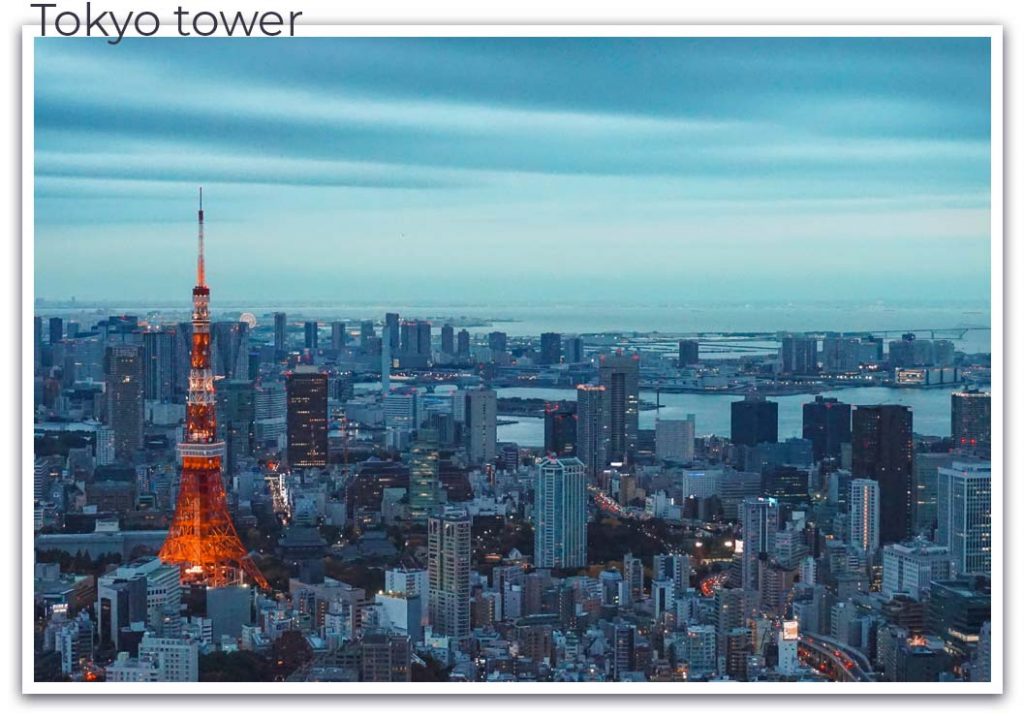

Wrapping my complimentary red kimono around me, I settle into my window seat in the Prince Gallery Tokyo Kioicho hotel and gaze down at the city’s sparkling lights laid tantalisingly before me. Despite being hermetically sealed into a glass tower, I can sense the energy and imagine the lives of over 37 million people playing out below. It’s oddly comforting to feel a part of this human stew, though I’ll only be here for a day and a half – hardly enough time to do the world’s biggest city justice.

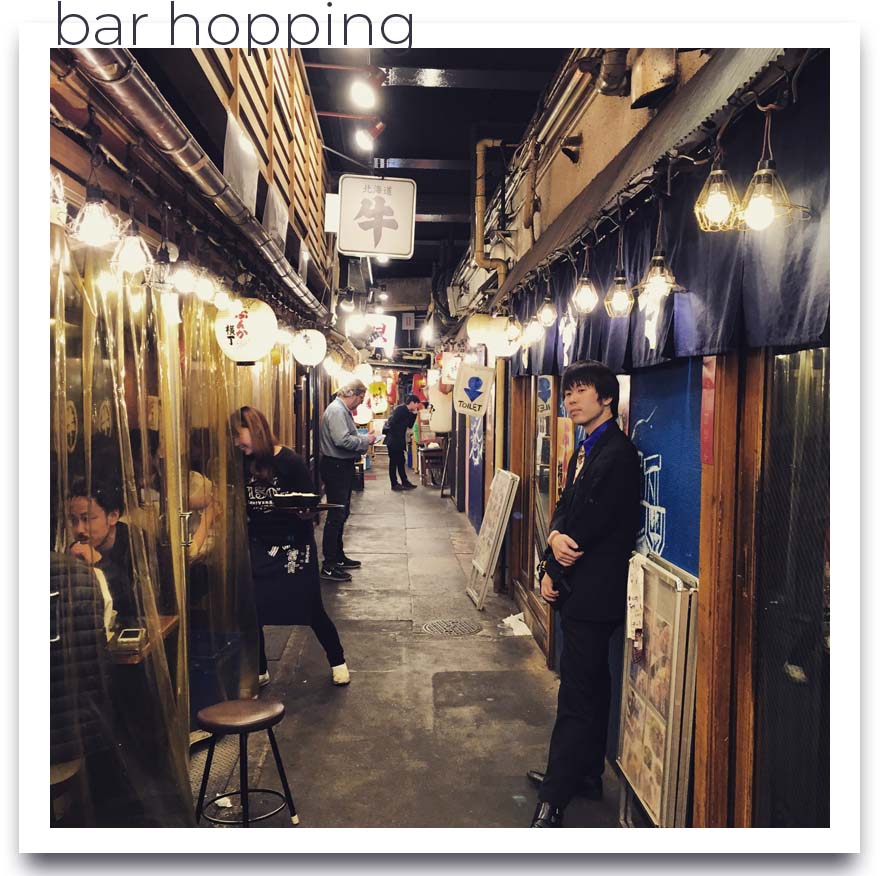

For dinner, my colleagues and I leave our glass tower to dine down to earth, under the railway tracks near Yurakucho station. Sandwiched between the upmarket apartment stores of Ginza and the Imperial Palace complex, this dense alleyway is stuffed with cheap eats. As soon as we enter, mouth-watering smells of smoky chicken wafts from yakatori stalls. We’re heading to an izakaya, a pub that serves food, explains our guide. Inside the Izakaya it doesn’t feel like a pub, in the British sense at least, apart from the line of single men sitting up at the bar. “That’s where the salarymen sit,” our guide explains, referring to Japan’s most famous stereotype – the hard-working, male white-collar worker who gives their life and soul to the office.

Soon our beer crate table is overflowing with fruity shōchū cocktails, bowls of edamame beans, curried chicken and noodle salad. The waiter reaches through the plastic hangings from the alleyway to add finely sliced rare beef before we move next door for seafood. This place is packed out with ravenous Tokyo marathon runners, eating under bare light bulbs while fish circle in tanks awaiting their fate.

Finally I understand why people rave about sushi. The thick cuts of dark red tuna are incredible but the orange uni, or sea urchin, which has a creamy oceanic taste, has me undecided.

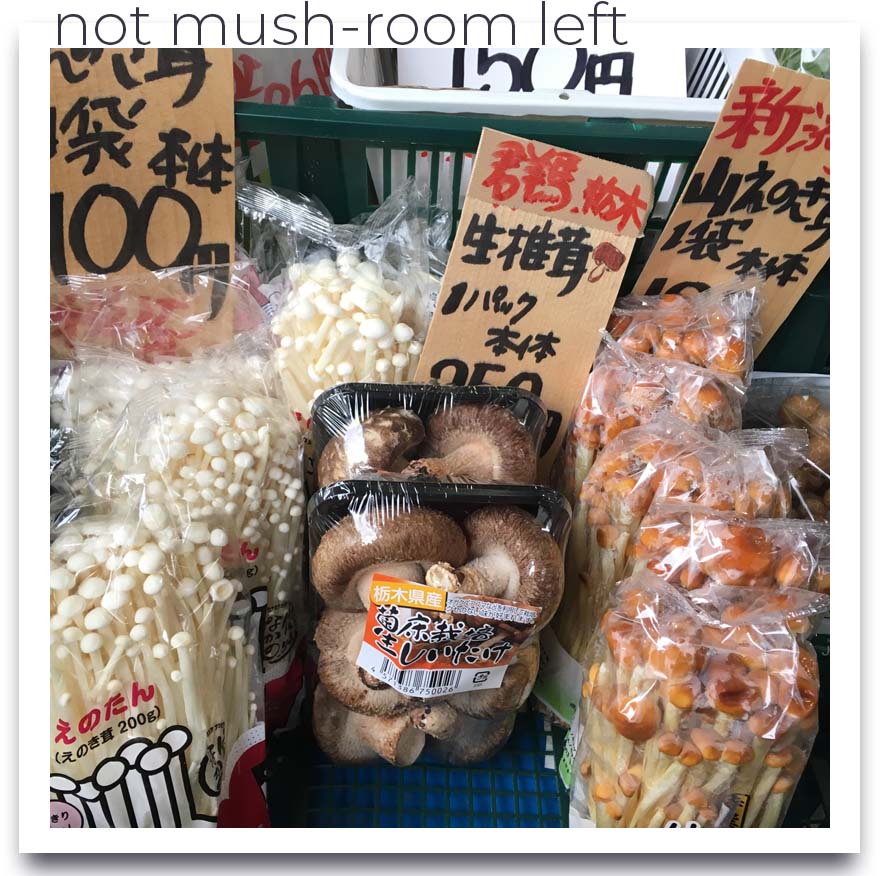

The next day continues with a fishy theme at Tsukiji Market. The wholesale section, famous for its auctions of huge tuna, has moved but the outer market remains and has a dizzying array of stalls and restaurants, most specialising in seafood. The varieties are astounding and I see lots of cartoon whales indicating that cetaceans are firmly on the menu. We’re told the wholesale market used to process 1,628 tonnes of seafood worth around $14 million every day.

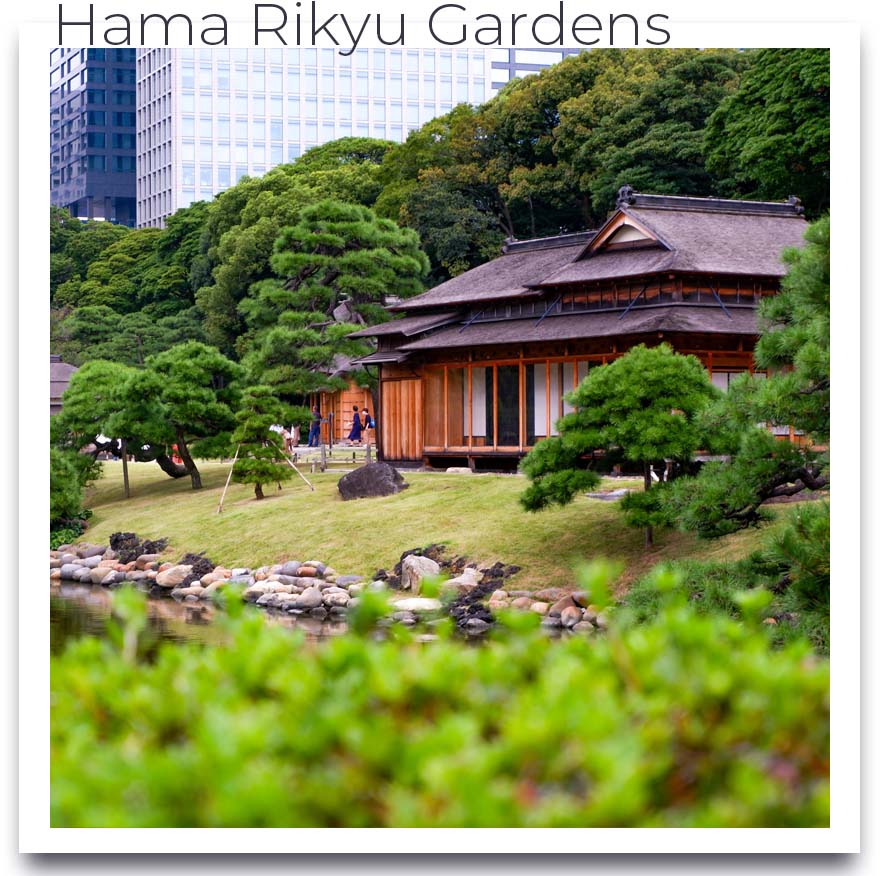

Our tour continues amongst the peaceful Hama Rikyu Gardens next to Tokyo Bay. The park was a feudal lord’s home and a duck hunting ground during the Edo Period (1603-1867) but is now fringed by the skyscrapers of the Shiodome district. It’s a tranquil haven from the frantic city pace outside, with traditionally styled gardens sloping gently around seawater ponds which change with the tides and a teahouse on an island.

From here, we hop on a water bus up the Sumida River to Asakusa. As we dock the city’s tallest building, the 634-metre Tokyo Skytree, looms above and across the water is the headquarters of Asahi beer, with its famous golden flame sculpture.

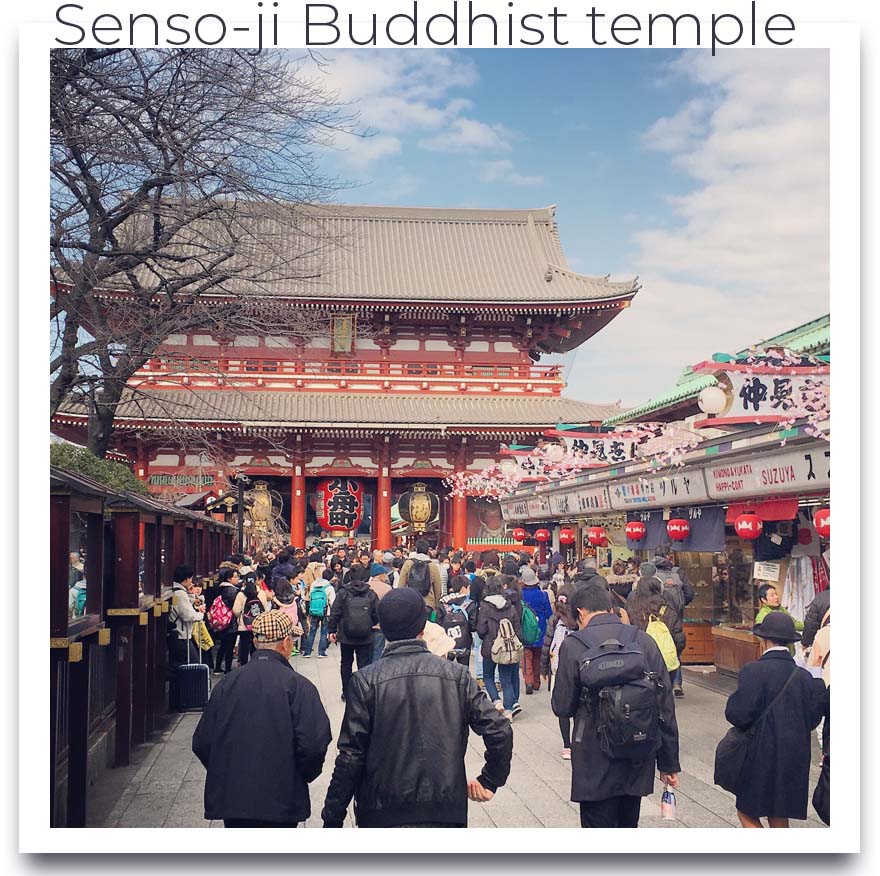

The Buddhist temple of Senso-ji is the oldest in Tokyo and the streets outside are packed. To get to the five-storey red pagoda we pass through Thunder Gate and under a giant paper lantern, looking above to see the carved wooden dragon at its base, and up the shopping street of Nakamise-dori which is lined with nearly 100 stores selling crafts, souvenirs and snacks. Inside the temple area clouds of perfumed incense rise from a giant cauldron and people stand bathing in it – it’s said to cure ailments – before they step up to the shrine to pray.

Many people in Japan practise Buddhism and Shintoism simultaneously but it’s the latter that is the indigenous religion of Japan and Meiji Shinto Shrine is our next visit. The temple is right next to Harajuku, a notoriously hectic area and a shrine of sorts itself, to Japanese youth culture. We take a walk down Takeshita Street to soak up the bonkers mix of cosplay shops, cat cafes and wacky multicoloured waffles. If you want to dress like a ‘Lolita goth’ and eat unicorn candyfloss this is the place!

Peace at last

The Meiji Shinto Shrine could not be more of a contrast. It’s set in a forest oasis just across the road and as soon as we pass under the wooden torii gate a sense of peace descends and we enter the realm of the kami (spirits). It’s as if the long tree-lined path gives you time to unplug from modern distractions. There are 100,000 trees here, donated from across the country, and the green roofed temple buildings seem to melt into them. Beautifully painted sake barrels, gifts donated by the makers, are displayed at the entrance and inside rows and rows of wooden tablets called emas inscribed with prayers and wishes, hang under a sacred tree.

Our guide explains that Shintoism doesn’t acknowledge an afterlife, which is why many Japanese practise Buddhism too. There’s no conflict or shame at this dual faith system – Senso-ji even had helpful signs reminding patrons that clapping is for Shintoism and bowing is sufficient in Buddhism.

Crossroads to the past

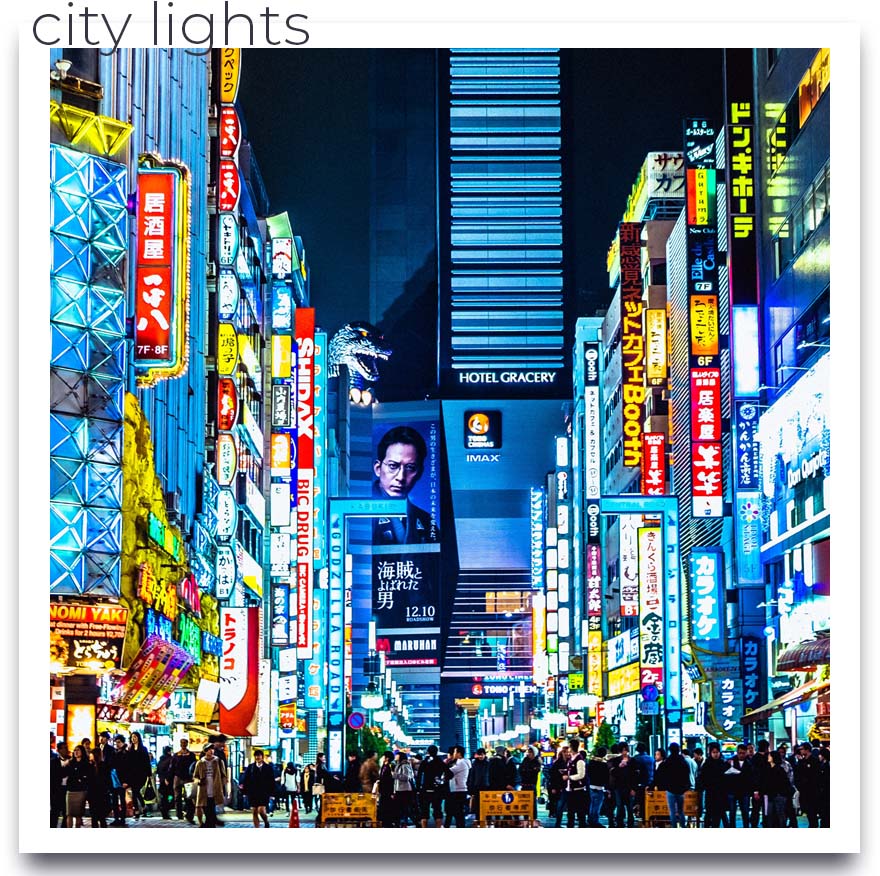

We are thrust back into city life as we mingle with the masses at the world’s busiest pedestrian crossing in Shibuya. Overlooked by vast flashing TV screens and skyscrapers, we scramble across the five-way intersection with thousands of others and it’s strangely thrilling.

We finish our day in Golden Gai, a bar district which escaped modernisation and is a pocket of 1960s Tokyo. Narrow alleyways are stuffed with some 200 bars, some holding no more than five patrons at a time and with just a curtain for door. Not all welcome foreigners but we pick a door and climb the narrow stairs to a warm welcome from a very smart bar man in a tailed suit.

As the night progresses and the drinks flow, the charming Nobu serves us complimentary plates of fine comte cheese and less fine cheesy puffs and reveals he is a guitarist and composer by day. As a musical man he may have regretted letting us loose with his percussion instruments but he grabs a triangle and joins in with a rousing accompaniment to Hey Jude, which draws a couple in off the street and fills the tiny bar.

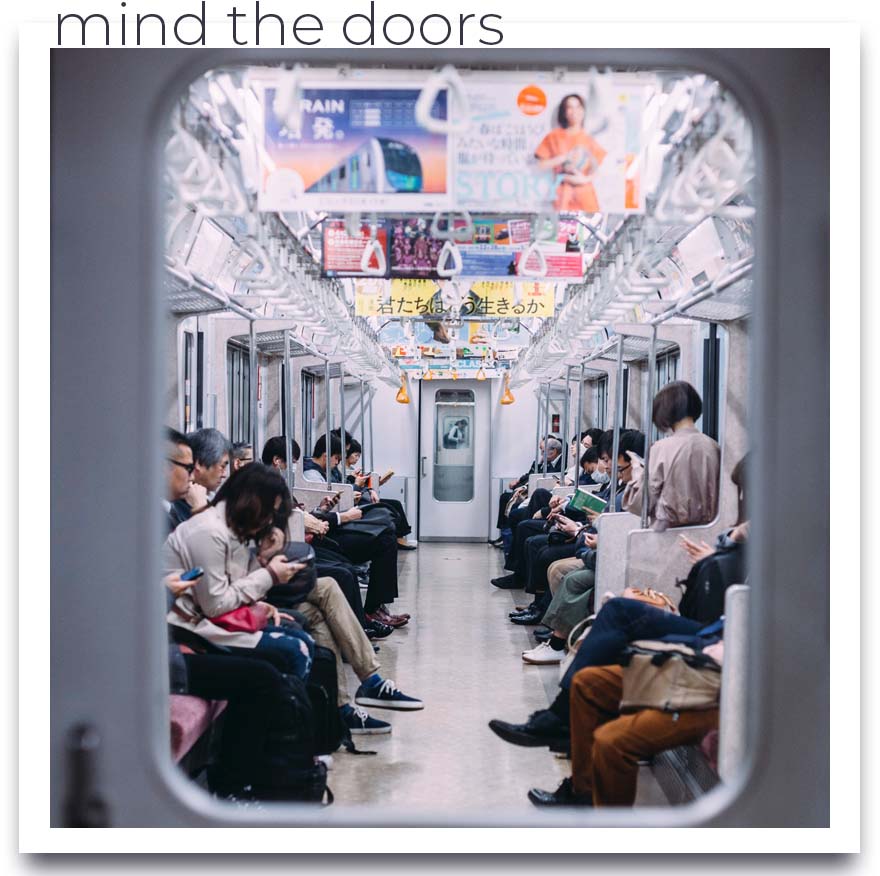

When we stumble out at 3am I turn to take a photo and find I cant identify which non-descript door we came from – it’s as if it has melted away and Nobu was a figment of our imagination. Leaving the next day I encounter a robot assistant on the Tokyo Metro who bows to me. It seems to sum up the bundle of contrasts that make up this city. The overload of technology which seeps into every corner of life (including the toilet) comes with a steadfast refusal to abandon tradition, but somehow it works, and it makes the future less alarming for a tech-phobe like me.

This is a feature from Issue 7 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

by net effect

by net effect