I’m pretty sure the iguana is dead. I glance at my friend, Mick, wondering if he’s thinking what I’m thinking. He looks as bemused as me as more children gather around, excitedly poking the poor thing through the cage with sticks.

“This lizard is deceased,” I hiss to Mick out of the corner of my mouth. “No, no it’s just resting,” he retorts. I knew he was a Monty Python fan. “This is an ex-lizard,” I say. At this point we start to fall about laughing, much to the amusement of the kids. We can’t really explain to them the parallel between their pet reptile and Monty Python’s famous dead parrot sketch because they’d never understand – the children don’t speak English and live on a tiny island in the remote San Blas archipelago, part of the Guna Yala region in Panama.

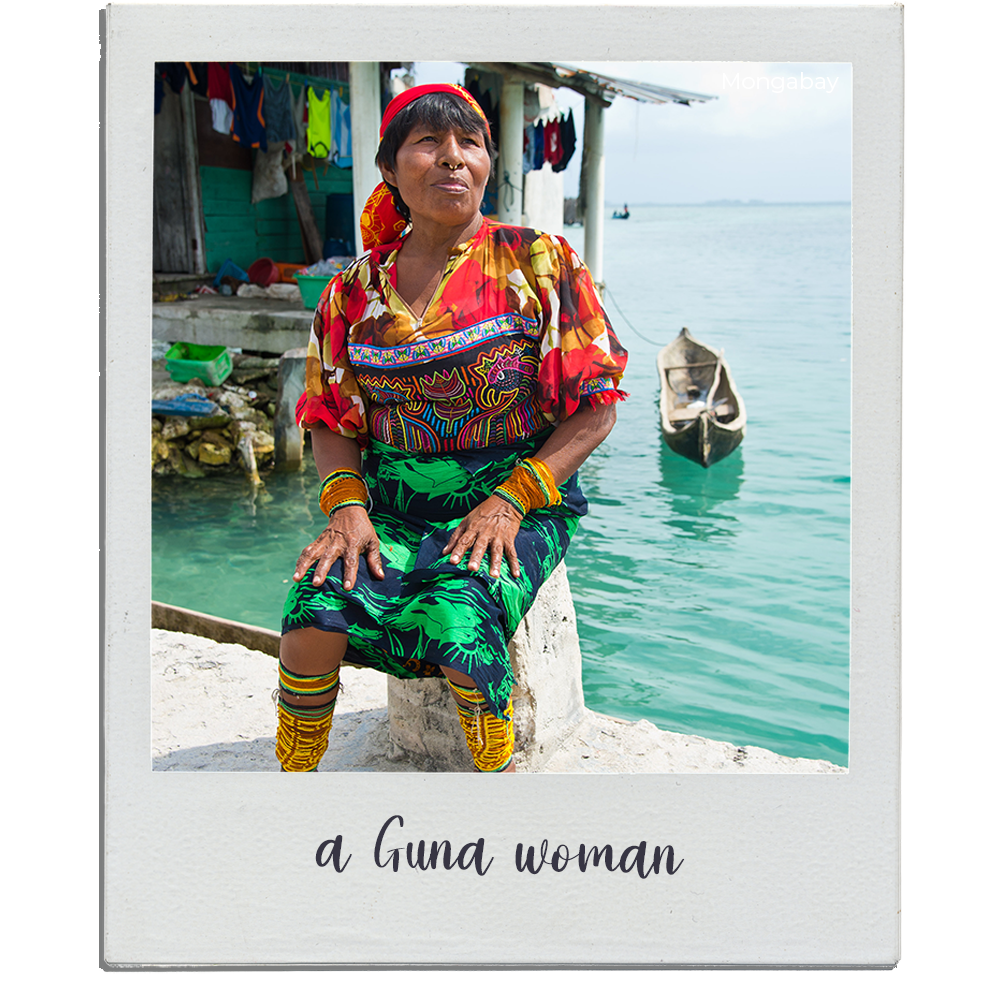

Guna Yala is the nation of the Guna people, an indigenous group small in stature but big in spirit. The Guna are one of Panama’s seven native tribes and fought to have autonomy over their land, which includes a 232-mile long strip of the Caribbean coast from the Colombian border. Most of the Guna live in the San Blas Islands but climate change is forcing them to look shoreward where a town is being built on higher land.

We’re on one of the four main inhabited islands, Gardi Sugdub, where around 2,000 people live, despite it being just 400 metres long and 150 metres wide. Every inch of space seems to be filled and the houses, fashioned from corrugated iron, reeds and bamboo, extend out over the water in place

As we cross the island we happen upon two nattily-dressed Mormons, who wave at us cheerfully, their black suits and crew cuts incongruous next to a local woman hanging out her washing. Like most Guna women, she’s dressed in vivid clothed sewed with molas, colourful embroidered squares of fabric. I’m dubious about how much impact the Mormons have had on this matriarchal society and as we duck into a hut to attend a puberty ceremony, I’m thinking… not much.

Held to mark a girl’s coming of age, it’s attended by a large crowd. Within the palm walls it’s dark and a bit steamy and everyone, including teenagers, are drinking a boozy brew of fermented sugar cane as a storm gathers outside. The Guna have welcomed Mormonism, our guide explains, but they still have their traditional beliefs, which are strongly rooted in nature, and continue to be wholly accepting of transgender members of the community – they call it the ‘third gender’.

The next day I awake on Aguja Island and find I have arrived in the Caribbean of my childhood drawings, a place where tiny white-sand islands glint on every horizon, some festooned with just a single palm ruffled by the salty breeze. There are no high-rise hotels – just tiny guesthouses offering beds in basic wooden huts. There are no sun-loungers, just solar-faded hammocks strung up between palm trees.

And there’s no Starbucks, Häagen-Dazs or any other brands, just fresh seafood delivered by dug-out canoe and served with coconut rice.

We pick a few islands at random, snorkelling to shore through turquoise water and picking our way across bleached driftwood, coconut husks and pink conch shells to ramshackle huts to meet the smiling Kuna owners, who are always happy to share their paradise if we take a look at their molas for sale.

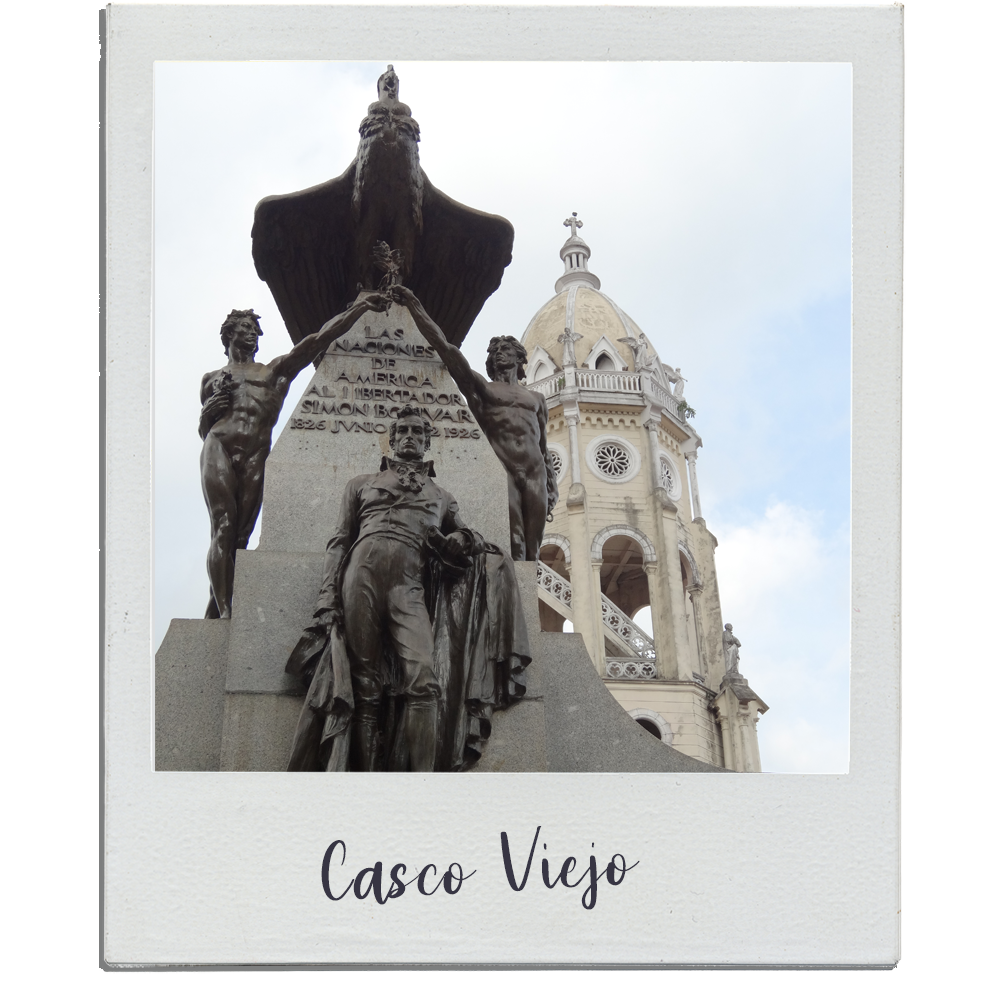

We don’t want to leave Eden, but the capital calls us back. Panama City has been around since 1519 and was the first Spanish settlement on the Pacific side of the Americas. It was this decision, along with it’s narrow geography, which sealed it’s fate as a strategically important spot. The ruins of Panama Viejo are all that’s left of the city’s first site, where tonnes of Incan gold passed through in the 1500’s on it’s way to Spain. After a ransacking by Sir Francis Drake, privateer Henry Morgan pillaged the city and razed it to the ground. It was reborn in what is now known as Casco Viejo, or the Old Quarter.

This is Panama City’s jewel, a compact maze of narrow streets and pretty plazas with pavement cafés begging to be frequented. Around each corner are grand churches, market stalls selling Panama hats and streets of distressed buildings, with pink, ochre, and green paint peeling behind sprays of bougainvillea. The tide of gentrification is obvious in t boutique hotels like Casa del Horno, but from the balcony of it’s penthouse suite, with hip exposed brick walls, I can see into the disintegrating slim opposite where little kids play.

The most beguiling thing about Casco Viejo it it’s juxtaposition with the new Panama City. From the cool rooftop bar of hotel Tantalo, we sip a mojito and gaze upon the sparkling skyline of the modern city across the bay. Stand-out skyscrapers are the crazy corkscrew of the El Tornillo building and the sail-shaped JW Marriott, the highest tower and once Donald Trump’s Ocean Club Hotel and condos, which was accused of being a centre for Colombian cartels to launder their drug money.

Being a tax-haven at the crossroads of the Americas means Panama has always drawn less than scrupulous types – like the infamous Brit John Darwin, who faked his own death via canoe accident and came here to live off his own life insurance. Let’s just say that the capital attracts characters.

In a café I get chatting to a nice American who claims to be one of the CIA Agents who captured Panamanian despot Manual Noriega in 1989. Now retired and en-route to the Caribbean isles of Bocas del Toro, he’s sporting a Hawaiian shirt and a novelty baseball cap and shows how much has changed here since Noriega – dictator, rouge CIA spy, and drug trafficker – was in charge.

Panama City is an interesting mishmash of cultures. The population are mostly of Spanish or Indigenous descent, but many have African heritage and there’s a big Chinese community. Much of this multiculturalism comes from the building of the Panama Canal, one of the world’s man-made wonders. Watching monster container ships pass through Mira Flores Lock strangely absorbing. Nearly 14,000 ships cross the 80km canal every year, taking four hours, displacing 220 million litres of water per ship and generating millions of dollars.

It’s worth visiting the lock’s museum to understand the human cost of building in a yellow-fever infested swampland, and the extraordinary efforts that go to thwarting nature’s attempts to reclaim it.

The canal was partly created by nature, since the Chagres River already existed. But the building of it created Gatun Lake, now the site of eco-resort Gamboa where we spend a day spotting wildlife. It’s just an hour from the city but on a boat trip we see capuchin and tamarin monkeys hanging from the trees, iguanas scampering the banks and crocodiles lurking offshore. Even inside the resort grounds capybara rambled and we glimpse a blinking sloth dangling from a tree. In nearby Soberanía National Park it feels a thousand miles from the city and we walk in hushed silence through the jungle, spying the silhouettes of toucans flitting above.

After a one-hour flight from Panama City we arrive in another world, the Chiriquí Highlands. Boquete is the base for exploring Panama’s coffee region and the air is pleasantly cool as we drive through misty valleys and past the rushing torrent of the Rio Caldera.

The river runs off Volcán Barú, a dormant volcano and Panama’s highest point. It’s the fertile volcanic soil which helps make the coffee world-class, but it also boosts the vegetable patches of strawberries, onions and cabbage which adorn every local’s garden and the flowers that run riot at the side of the road. It’s no wonder this lush and beautiful place is so popular with retired expats and we meet many in the local cafes, sipping coffee without a care in the world.

The area’s most famous flower is the angel’s trumpet. Peach and cream coloured, they hang like magical ornaments from every wall at hotel Finca Lerida, where I spot the blur of a hummingbird. I could stay here all day, listening to the rain and looking out for the flash of green and red which signals the resplendent quetzal bird, but it’s time to wake up and smell the coffee.

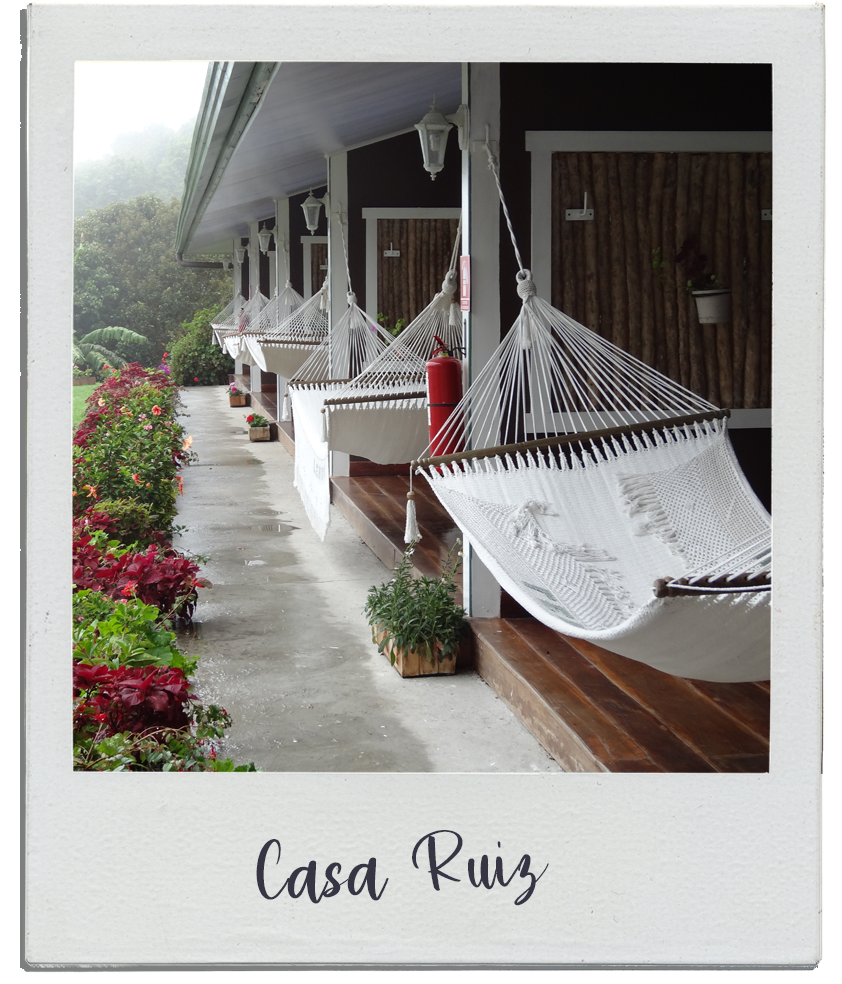

At plantation Casa Ruiz we take a bean-to-cup tour from another of Panama’s characters, Carlos. It’s not his encyclopaedic knowledge of coffee, or his passion for the organic environment in which the beans grow here, amongst mango, guava and avocado trees, but his insight into Boquete living that provides the entertainment. He asks us, mischievously, what Boquete’s most common bird is. According to Carlos it’s the snowbird – that not-so-rare breed of retired North American who flies south for winter to nest in this beautiful place. I can’t say I blame them.

Indigenous groups like the Guna are threatened by climate change and habitat destruction. Survival International works with them to amplify their voice and save their way of life.

survivalinternational.org

This is a feature from Issue 5 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

Fundraising Futures Community Interest Company, Contingent Works, Broadway Buildings,

Elmfield Road, Bromley, Kent,

BR1 1LW. England

Putting our profit to work supporting the work of charitable causes

For the latest travel advice, including security, local laws and passports, visit the Foreign & Commonwealth Office website.

© 2024 All rights reserved

Made with

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELB | session | Associated with Amazon Web Services and created by Elastic Load Balancing, AWSELB cookie is used to manage sticky sessions across production servers. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |

| JSESSIONID | session | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __lc_cid | 2 years | This is an essential cookie for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __lc_cst | 2 years | This cookie is used for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __oauth_redirect_detector | past | This cookie is used to recognize the visitors using live chat at different times inorder to optimize the chat-box functionality. |

| aka_debug | session | Vimeo sets this cookie which is essential for the website to play video functionality. |

| player | 1 year | Vimeo uses this cookie to save the user's preferences when playing embedded videos from Vimeo. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 6 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_164521185_1 | 1 minute | This cookie is set by Google and is used to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| _hjid | 1 year | This is a Hotjar cookie that is set when the customer first lands on a page using the Hotjar script. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description available. |

| CONSENT | 16 years 3 months 16 days 17 hours 23 minutes | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. They register anonymous statistical data on for example how many times the video is displayed and what settings are used for playback.No sensitive data is collected unless you log in to your google account, in that case your choices are linked with your account, for example if you click “like” on a video. |

| iutk | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is used by Issuu analytic system. The cookies is used to gather information regarding visitor activity on Issuu products. |

| vuid | 2 years | Vimeo installs this cookie to collect tracking information by setting a unique ID to embed videos to the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Google DoubleClick IDE cookies are used to store information about how the user uses the website to present them with relevant ads and according to the user profile. |

| mc | 1 year 1 month | Quantserve sets the mc cookie to anonymously track user behaviour on the website. |

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |