There’s a story being acted out in front of me which no one seems able to explain but it involves a cowboy riding a ragged pantomime horse made from a white sheet, a creepy doll with a hole in it, the devil, some big coconuts and a man having a retro telephone pulled out of his backside. In terms of making an impression, Sao Tome is really nailing it – and I haven’t left the airport yet.

We flew via a grey November Lisbon and stopped at a steamy Accra before arriving as the sun set. The island’s coast looked wild and wicked from above, with black rocks dashed by white waves; the interior mercilessly green, with thick jungle and velveteen hills.

The airport was cramped and basic and the fresh air outside a relief but the heat is settling around me like a blanket now, and the frenzied drumbeat and shrieking whistles ring in my ears. There are about 30 masked dancers and musicians, some in green and white silk costumes with colourful carnival-esque headdresses; some just wearing ragged shorts and shirts with freaky masks – one man has improvised by strapping a ripped-up beer box to his face. Without a local to hand the story is left unexplained, so I just take it as ‘welcome to Sao Tome’.

The following morning, I awake in my hotel to sunshine, palm trees and a tempting strip of beach under my balcony and the arrival seems like a dream. Sao Tome and Principe is my first foray into West Africa and all I know so far is that it’s dubbed the Galapagos of Africa. The twin-island nation is an ex-Portuguese colony, sprouting out of the Atlantic Ocean around 450 miles off Gabon.

After being discovered in the late 1400s it became a major exporter of sugar cane, worked by slaves shipped in from across the African continent. After a decline in production and brief Dutch rule, the Portuguese re-took the islands and introduced cash crops of coffee and cocoa. Sao Tome and Principe became independent in 1975 and it still produces these. The plantations will have to wait though, because my visit is starting in the island’s eponymous capital.

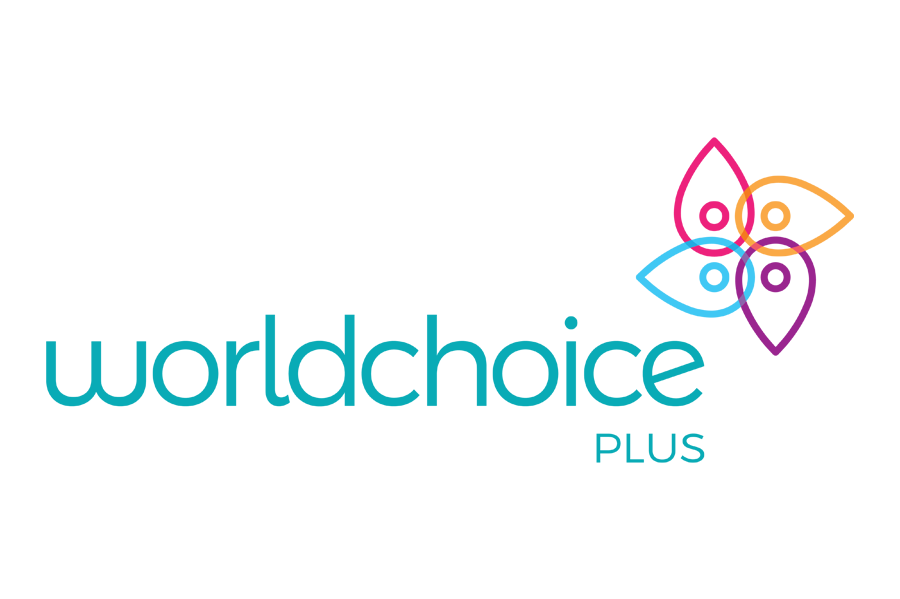

Our first stop is the weather-beaten Fort Sao Sebastiao, which is fronted by rusted mooring posts that look like rotten teeth bared to the sea. Archaeological decay is evident everywhere, in the faded grandeur of the pastel pink Town Hall, with its peeling green shutters and moulded balustrades, and in the dark confines of the city’s market.

Here, I pick my way over a wet concrete floor. Mould is creeping up the walls, the electricity is dead and only shafts of daylight cracking through the roof light the room, giving it a jaundiced look. My male companions hover protectively but it’s safe and we get a warm welcome from the beaming owner of a knock-off t-shirt shop.

Outside the market is like 4D technicolour in comparison – shouting, beeping cars, a whistling policeman, fish blood running in the gutters, flies buzzing over meat, the smell of warm, ripe fruit and dazzling colour – from the produce and from the women selling it in their bright African prints, shaded by vivid umbrellas.

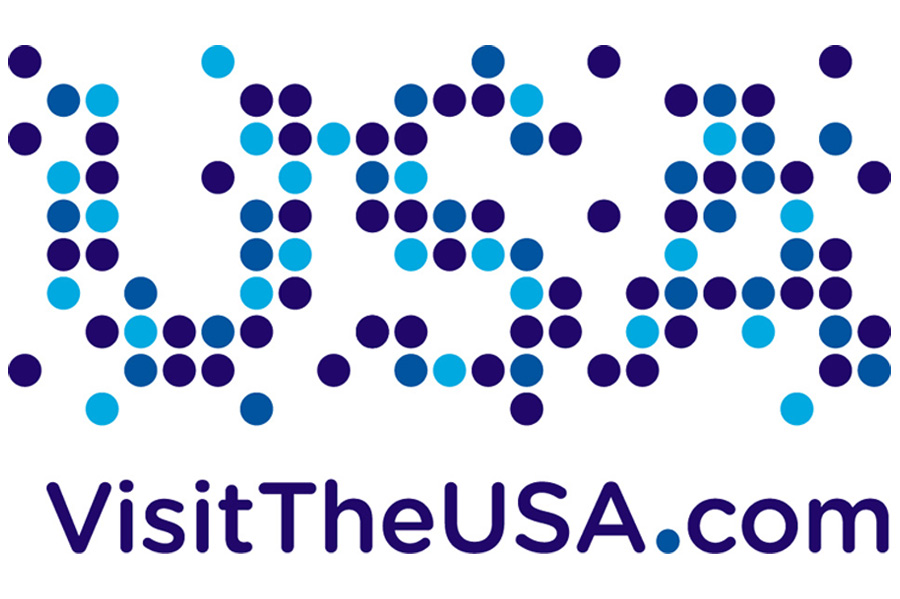

Heading north out of town, we whizz past numerous roadside villages with tin-roofed shacks and almost bare shops displaying single bunches of bananas or a few tots of the local tipple, palm wine, which is sold in recycled plastic bottles. Our guide surprises us with two musical performances – dancing school girls meet us in a playground, grinding their hips like Rihanna with a nonchalant air. And later, singing women of Cape Verde descent surprise us at the side of a once grand, poker-straight road on former plantation Agostinho Neto. Afterwards, we follow the broken concrete to a derelict hospital where squatters’ washing flutters from the gutted windows and drapes over the once elegant curved staircase.

The next day we head south and happen on the wild coast I spied from the plane. Boca de Inferno, or Hell’s Mouth, is the first photo stop. This striking black rock promontory curls into the ocean like a comma, its circular bulk surrounded by a boiling sea and occupied by a lone fisherman in a red t-shirt. We stop for lunch in Sao Joao Anglares, a village at the centre of Sao Tome’s distinct Angolares community, a group of fishing people who speak their own language and are descended from runaway slaves. Restaurant Mionga overlooks the mangroves, the black sand flats of the river and the ashen beach and sea beyond. The only sounds are the faint shouts of fishermen and the wind in the palms as we eat fried fish and plantain with rice.

As we head further south the villages are sparser and the roads increasingly potholed. Then the palm oil plantations begin, at first blending insidiously with the indigenous vegetation until I notice how perfectly planted they are, like soldiers lined up between the mountains and the road.

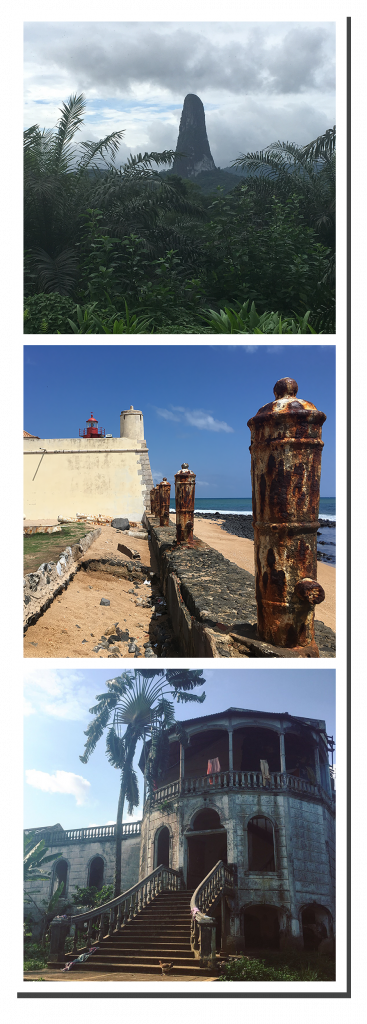

We round a bend and, like a giant finger, Pico Cao Grande pokes the heavens defiantly. The 386-metre volcanic plug peak is apparently treacherous – slippery with moss, more often than not veiled in mist, surrounded by thick ferns and vines and ‘an abundance of snakes’, some of which inhabit the dark tower itself Apparently, climbers have been known to scale it though.

We catch an overcrowded boat to Ilheu das Rolas and its four-star Pestana Resort, feeling like we’re on holiday instantly thanks to cold towels on arrival, wood chalets and a huge pool – the largest in West Africa we’re told – where we watch the sun sink into the sea bang on 6pm. The island lies directly on the equator and in the morning, we take a walk through the jungle, past sleeping pigs, to the centre of the earth, posing for silly pictures on a tiled world map which is laid out on the forest floor but slowly being reclaimed by it, like many man-made constructions in Sao Tome.

Guests are free to walk beyond the hotel and I have a banana-shaped beach to myself one morning and spend an afternoon as the sole tourist on another, watching some men load their boat with coconuts under moody skies.

Back on the main island, we pass more abandoned plantations, or rocas as they are known. We stop at Roca Agua Ize, which still produces cocoa, albeit in much smaller quantities. Sacks of cocoa beans are stacked in the vast warehouses, lit by dusty shafts of natural light. The grand house itself is a gutted shell but a group of children that live in the ruins take my hand and lead me up the grandiose staircase to proudly show me the million-dollar sea view from their roof terrace.

Lunch is at Casa Museu Almada Negreiros, named after the Portuguese artist and built on the site of his former home. The restaurant and museum is in a wooden house, an open terrace perched above the green trees where we are served traditional cuisine, beautifully presented by a team of proud local chefs.

My last night is spent in the luxury of the Club Santana Resort, where I eat Brazilian-style barbeque, take a bamboo stick stretching class and lounge on a black sand beach watching little fishing boats pass, their single square sails fluttering. Sao Tome is not your average holiday destination and at times the poverty and decay can be upsetting. It’s visited by only a handful of tour operators but it has so much more to offer than what I’ve seen. Sister island Principe for starters, which is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

But the image of decline I’ll take with me is a comforting one. It seems to me that it’s Mother Nature who’s painting the roca walls in moss, snaking her arms treacherously through roofs and sprouting green tresses defiantly out of glassless windows. It’s an inevitable but atmospheric repossession – justified revenge on the colonists – and will be my abiding memory of Sao Tome.

This is a feature from Issue 4 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

Fundraising Futures Community Interest Company, Contingent Works, Broadway Buildings,

Elmfield Road, Bromley, Kent,

BR1 1LW. England

Putting our profit to work supporting the work of charitable causes

For the latest travel advice, including security, local laws and passports, visit the Foreign & Commonwealth Office website.

© 2024 All rights reserved

Made with

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELB | session | Associated with Amazon Web Services and created by Elastic Load Balancing, AWSELB cookie is used to manage sticky sessions across production servers. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |

| JSESSIONID | session | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __lc_cid | 2 years | This is an essential cookie for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __lc_cst | 2 years | This cookie is used for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __oauth_redirect_detector | past | This cookie is used to recognize the visitors using live chat at different times inorder to optimize the chat-box functionality. |

| aka_debug | session | Vimeo sets this cookie which is essential for the website to play video functionality. |

| player | 1 year | Vimeo uses this cookie to save the user's preferences when playing embedded videos from Vimeo. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 6 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_164521185_1 | 1 minute | This cookie is set by Google and is used to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| _hjid | 1 year | This is a Hotjar cookie that is set when the customer first lands on a page using the Hotjar script. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description available. |

| CONSENT | 16 years 3 months 16 days 17 hours 23 minutes | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. They register anonymous statistical data on for example how many times the video is displayed and what settings are used for playback.No sensitive data is collected unless you log in to your google account, in that case your choices are linked with your account, for example if you click “like” on a video. |

| iutk | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is used by Issuu analytic system. The cookies is used to gather information regarding visitor activity on Issuu products. |

| vuid | 2 years | Vimeo installs this cookie to collect tracking information by setting a unique ID to embed videos to the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Google DoubleClick IDE cookies are used to store information about how the user uses the website to present them with relevant ads and according to the user profile. |

| mc | 1 year 1 month | Quantserve sets the mc cookie to anonymously track user behaviour on the website. |

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |