Room to Roam: Conservation in Africa

Finally starting to get the recognition it deserves, the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Park – KAZA – is a bold conservation project spanning five African countries. Wildlife photographer and writer Mike Unwin takes us on a tour

This is a feature from Issue 19 of Charitable Traveller.

An hour into our morning game drive and we’ve come to a halt.

Moments ago, the hoarse alarm bark of a baboon suggested a predator was in the vicinity – a suspicion confirmed when others joined in, quickly ramping up the outrage. Now we sit tight, straining eyes and ears. What? Where?

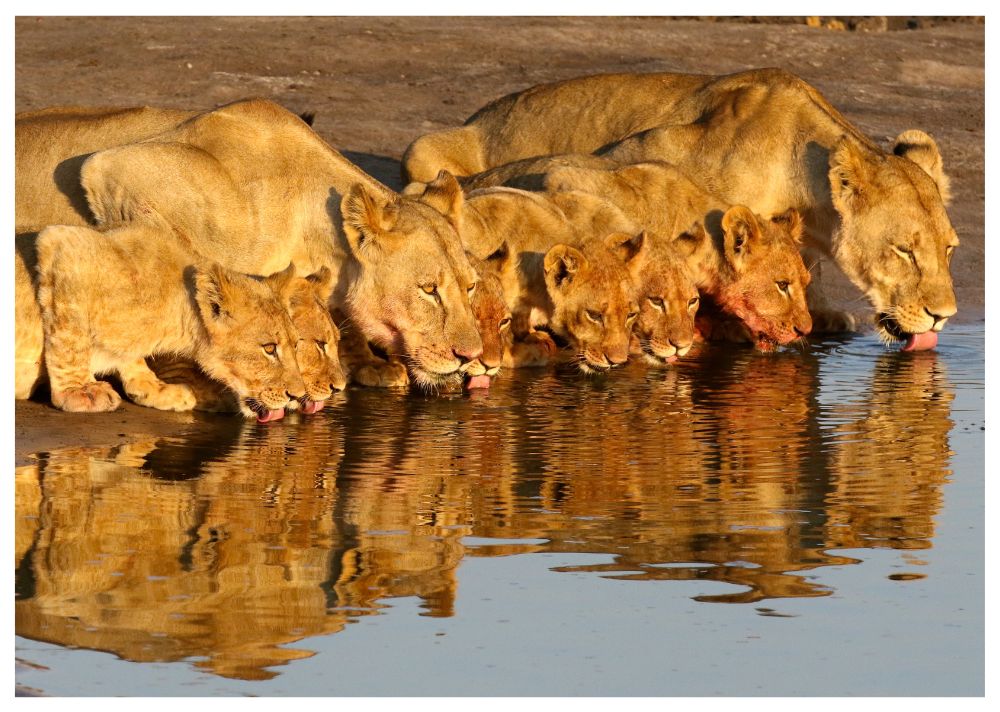

“Lioness,” mouths Lucius, our guide, nodding to our right. Sure enough, here comes the cause of the commotion, padding out of the thickets and across the dusty

track in front of us. Close behind comes her golden-maned suitor. He pauses to give a sapling his territorial dousing, fixes us with an amber glare, then pads on after his mate. The bush closes behind them, leaving just the subsiding protests of the baboons and our own unspoken awe.

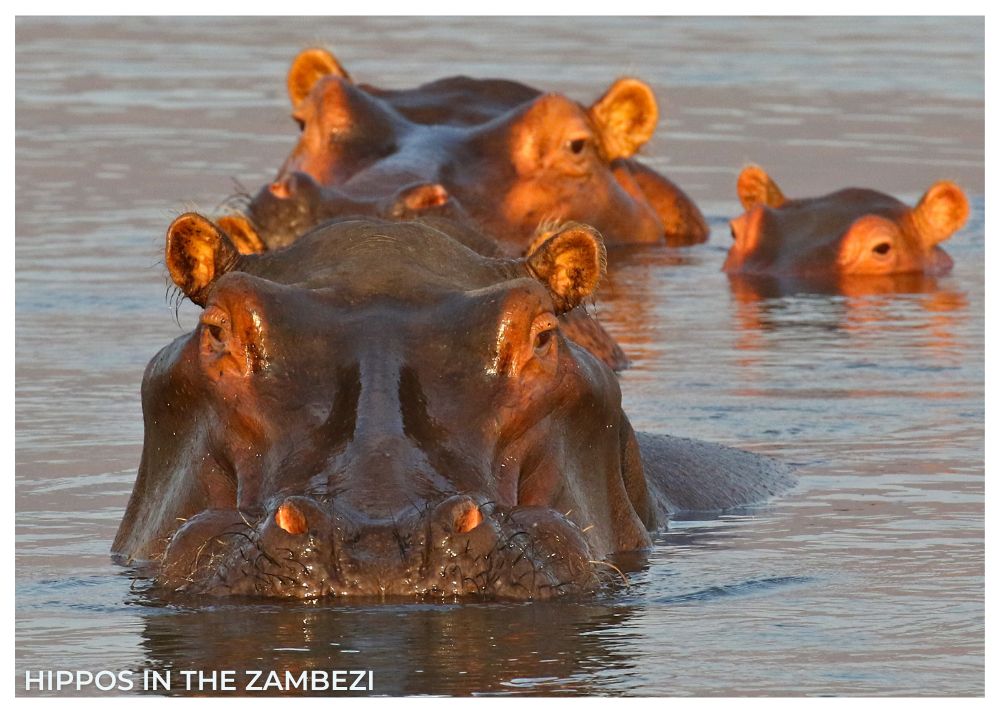

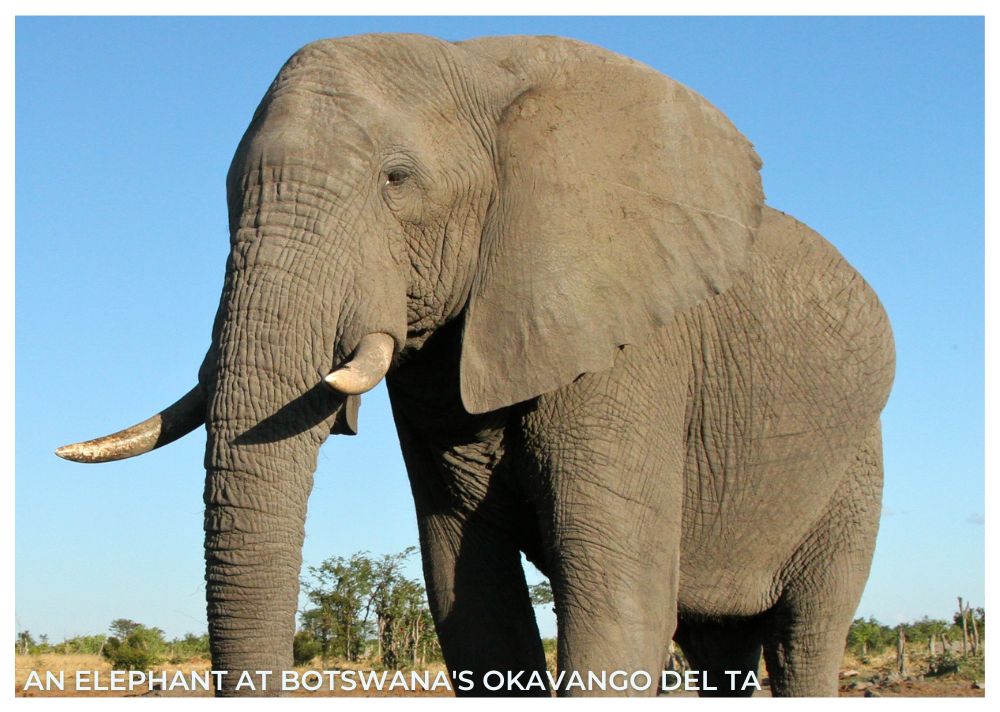

I’m in the little-known Nkasa Lupala National Park, a small reserve in Namibia’s Zambezi province – that narrow strip of land, formerly called Caprivi, in the country’s far northeast. This park is one of those classic ‘best-kept secrets’: most safari-goers to the region visit the more famous reserves of Botswana, just over the Kwando River immediately to our south. But in less than 24 hours here, we’ve seen elephants, buffalos, zebra, hippos and numerous antelope, not to mention a pageant of birdlife. Last night, I’d even heard the rasping grunt of a prowling leopard outside my safari tent.

Truth be told, it wasn’t always this way. The parks of Zambezi province had long been neglected, the victims of regional instability, heavy poaching and conflict with a burgeoning local community. Wildlife – especially larger mammals – had become thin on the ground, and with few facilities, it took a resourceful traveller to seek it out.

Today, things have changed, thanks to the birth of the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Park – otherwise known as KAZA. Nkasa Lupala is one of 36 national parks contained within this vast trans- national conservation area, which incorporates contiguous slices

of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Others include such world-famous reserves as Chobe and Hwange, plus celebrated World Heritage Sites such as the Okavango Delta and Victoria Falls. Between and around them are multiple smaller pockets of protected land. Altogether, this amazing wilderness jigsaw forms one expanse of 520,000 square kilometres; the size of France. That makes it the world’s second largest conservation area on land.

Creating Space

KAZA launched in 2011, with a mission to restore the region’s natural landscapes and depleted wildlife by linking existing protected areas, thus allowing elephants and other animals to resume time-honoured migration routes, unfettered by national boundaries. Through sustainable tourism and development, it also aims to improve the well- being of the local communities who depend upon this land. Today governments, NGOs, community members, scientists and conservationists from all five countries are on the case.

Our lions this morning offer impressive proof of progress. Sightings of these big cats, plus other large predators, are already on the up in Zambezi Province.

KAZA's mission is to restore the region's depleted wildlife by linking existing protected area, thus allowing animals to resume time-honoured migration routes

What’s more, tracking has established that many are moving back and forth across the Botswana border, some even continuing north across this strip of Namibia into Southern Angola. Elephant and buffalo have been following similar cross-border routes.

I talk to community leader Lembo Lameck about the new Kwando Carnivore project. He explains how local people, understandably, worry about animals living alongside that might trash crops or kill cattle. But this project is making a difference. For every tourist lion sighting, Nakasa Lupala lodge donates a fee to the community, which WWF matches. Meanwhile, KAZA has helped the village build 11 mobile lion-proof kraals (enclosures), which have both reduced attacks on cattle by 90% and fertilised the ground for planting crops.

Camera traps also help alert the community to lion movements outside the park. “Before, people were fighting lions like nobody’s business,” Lembeck tells me. “Now we’ve got a solution.”

Two days earlier and roughly 300 kilometres to the south, I was standing beside Botswana’s Boteti River hearing a similar story. There, cattle farmer Kelelo Aobakwe showed me the new solar panels that powered an electric fence around his property. “9.9 volts is enough to keep the elephants away,” he smiles. I asked him about lions. “When I see a lion, I see tourism.” The Boteti Riverfront borders Botswana’s Makgadikgadi Pans at KAZA’s southernmost edge. Here, the arid thorn scrub and blinding white salt pans are a world apart from the lush waterways of the Zambezi Region, but after the rains, this region attracts thousands of zebra from the north in one of

Africa’s greatest migrations. That evening, from the gorgeous Leroo La Tau lodge, we watch the herds mass along the river valley, joining wildebeest, giraffe and a scattering of elephant bulls in a sunset tableau that is pure timeless Africa.

We watch the herds mass along the river valley, joining wildebeest, giraffe and a scattering of elephant bulls in a sunset tableau that is pure timeless Africa

Across the Falls

Three days after leaving Nkasa Lupala, I’m on a forest trail getting drenched to the bone. The rainy season is still months away: this is simply the soaking afforded any visitor to Victoria Falls when the river is in full spate. Retreating to a sheltered viewpoint, I gaze out across the cataract’s thunderous 1.7km extent. I’m standing in Zimbabwe but looking into Zambia.

It’s another reminder that this region’s natural heritage transcends national boundaries; that the mighty Zambezi, which two days ago carried us by boat from Namibia into Zambia and is now crashing over the cascade in front of me, carries no passport. Neither do the 250,000 elephants that inhabit KAZA’s wilderness areas, some 44% of Africa’s total. Plans for a KAZA ‘uni-visa’ may soon mean that tourists can also traverse the region border-free.

Victoria Falls – known in Lozi as Mosi-oa-Tunya, ‘the smoke that thunders’ – is KAZA’s tourist hub, offering everything from booze cruises to bungee-jumping. To get an idea of what KAZA is doing behind the scenes, I explore on both sides of the river. In Zambia, I visit a sustainable agriculture project and patrol a township with a wildlife conflict team. In Zimbabwe, I enjoy the Vulture Culture Experience at Victoria Falls Safari Lodge, where these threatened raptors drop from the skies for their daily meal of bloody scraps, and visit the Victoria Falls Wildlife Trust, where scientists are using DNA forensics to combat wildlife crime across the region.

Our final morning has me drifting downriver on a dawn breakfast cruise. I reflect on how inspiring I have found KAZA; how, despite the sobering problems southern Africa faces, it offers a vision in which visitors to any of its magnificent parks will be putting something back for the entire region. But then, when you have a champagne cocktail in hand, hippos around your boat and the sun rising over the Zambezi, inspiration comes easily.

Get in touch with our expert travel agents today to plan your perfect safari holiday, and donate 5% of the price to the charity of your choice for FREE!

This is a feature from Issue 19 of Charitable Traveller.

by net effect

by net effect