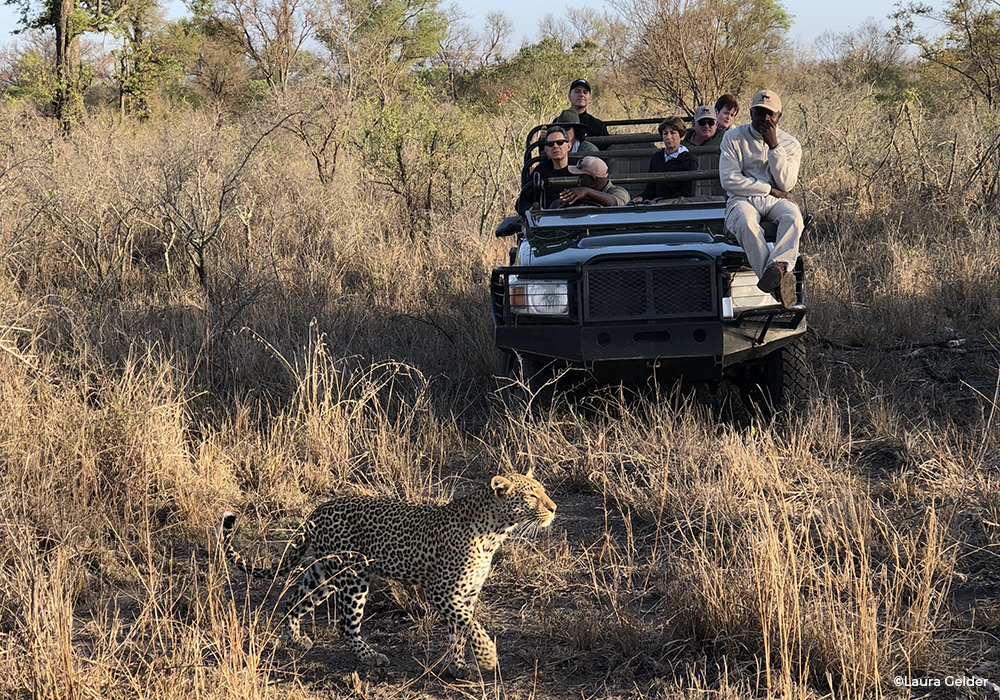

A first-time safari exceeds every expectation for Laura Gelder, as she learns the ways of the bush and discovers some unexpected and unsung heroes.

An alarm is sounding, shrilly cutting through the silence of the bush like an electric saw, but the leopard really isn’t concerned. I’m watching closely and a paw twitches, almost imperceptibly, but she stays stationary, her fashionably-patterned belly rising and falling gently as she pants in the already stifling morning heat.

The sound comes from a tiny bird, which flies in front of our jeep screeching at the top its voice and flapping its wings in a mad panic. It’s as if it’s saying: “What are you doing? There’s a massive leopard right there, get out of here – save yourselves!”

The drongo, our safari ranger Jaben tells us, is one of the security guards of the bush. They are always on hand to let smaller animals know when a predator is about.

It’s an unremarkable looking creature, small and black like a blackbird but with a forked tail, and not a bit as glamorous as the gloriously flashy lilac-breasted roller we spotted earlier. But I appreciate my plucky feathered friend’s warning, even if we are perfectly safe in our sturdy jeep with our rifle-wielding companions.

In Sabi Sands, the boundary between the raw natural world and the comfort of a holiday resort is always blurred. My boyfriend, his parents and I are staying in Simbambili Game Lodge, one of several on this private reserve in South Africa’s Greater Kruger National Park. Its luxurious stilted suites are dotted among dense stands of knobthorn and jackalberry trees along the current bone-dry Manyeleti River and perfectly placed opposite a water hole, artificially topped up by the owners, where animals gather to feed throughout the day.

Just a Drop helps to bring sustainable and safe water, sanitation and hygiene projects to communities across Africa and the rest of the world.

charitable.travel/just-a-drop

On the first evening, after dinner we venture out onto our private deck to gaze at the stars, which burn bright in the absence of street lights. We’re swaddled comfortably in the balmy night air but it’s not long before the peace is destroyed again, when an almighty crash signals the approach of something. We listen, frozen next to each other, our eyes straining into the black. The prolonged drought means the undergrowth is brittle and as whatever it is gets closer we stand back from the railings and listen to the snap, crackle and pop pass right by our noses.

The next morning our suspicions are confirmed, it was a herd of elephants looking for food, and they came so close we could probably have reached out and touched their leathery hides as they plodded by.

Apparently there’s a resident leopard here too, she was born under the resort’s decking and still likes to hang out here, hence the need for an armed escort between your room and the restaurant after dark. Two nights later, a guest nips back to her room to get some reading glasses and gets stuck when they find her sitting outside their door, a dangerous interpretation of ‘cat on the mat’.

I’ve never been on an African safari before but I’m instantly hooked. The day starts early, leaving at 5am to beat the heat. Jaben and Rodney, our tracker, drive us around the reserve looking for wildlife for a few hours before a sumptuous breakfast and a day of relaxing on the deck. Then, as the sun starts to dip and the intense heat subsides, we head out again, stopping only for a ‘sundowner’ – mine’s a gin and tonic and they make a mean one – until darkness falls completely.

For Africa provides food, education and healthcare to Africa’s most vulnerable children and they need more help than ever since Covid-19 arrived. charitable.travel/bread-and-water-for-africa

The principle aim is to see the Big Five – lion, leopard, rhinoceros, elephant and Cape buffalo – a term coined by hunters to describe the five most difficult animals to hunt on foot. Happily it’s now mostly used in safari vernacular and the feat is accomplished by seeing them, not killing them.

I can’t imagine why anyone would find any glory in killing any of the Big Five or any of the other captivating creatures, great and small, which we happen upon. The study of them is so endlessly rewarding and what really strikes me is how unexpected characters, like the Drongo, provide just as much fascination as the big guns of the bush.

We spend a whole hour, one sweltering afternoon, observing two hyenas in a stand-off over a dirty bone. The female sits in the middle of a muddy pool, guarding it under her paws and watching balefully as the male tries, unsuccessfully, to approach the situation delicately. In the hyena world, Jaben tells us, women are dominant. This is patently obvious as we watch him perform a cringing dance around her and 12 attempts at contact by sloping towards her in an obsequious bow. This gesture of courtship is rejected 12 times too and eventually she gets bored, retrieves her bone from the murky depths and trots off into the bushes. We follow for a while, all rooting for him, as he pursues her doggedly through the undergrowth, always at a respectful distance. They aren’t dogs at all though, we’re told, closer to cats and not dissimilar to bears in many ways.

I become slightly obsessed with these reviled scavengers and grow to respect them more and more as the days go by. Back at the plunge pool I read that female spotted hyenas were once thought to be hermaphrodites because they sport an enormously elongated clitoris, through which they urinate, copulate and give birth. Youch! This does have its up-sides though, it makes it challenging for a male to get his end away and it means she can change her mind after sex and flush his sperm out with her urine – genius and much easier than the morning after pill, I muse, while sipping a cold beer.

Of course, the Big Five impress too. Staring into the pale gold eyes of a young male lion, perched imperiously above us on a termite mound, is unforgettable. The size of his paws compared to my own cat back home is what I note, as he strolls casually towards us and slumps in touchable distance, using us in the charming way that only cats can for the shade our jeep provides, just as my Burmese Gabby would on a hot summer’s day in the garden. “They are just massive great cats,” I think out loud, and Jaben agrees kindly.

Elephants are ten-a-penny in Sabi Sands but we never tired of seeing them and a highlight is seeing a three-day-old elephant up-close. The mother and child peel off from the herd and parade right past us, seemingly in a show of bursting parental pride, mum’s trunk always curled protectively around her offspring’s wrinkled little bottom as it hurries beside her. It’s strangely emotional and I shed a tear behind my sunglasses for these almighty and humbling creatures. Later we find some male elephants crashing about in a thick swathe of bush and learn that young males often hang out in bachelor groups before they mate. A life-long animal lover and over-sensitive soul, I’ve always been prone to anthropomorphise but with elephants I can see that I’m not totally off the mark.

Simbambili is pure luxury and although we experience visceral nature out in the bush, I always feel cocooned. We don’t see any death – a lifeless impala being dragged up a tree by a determined pregnant leopard is the closest – but we often feel like we’re on the verge of observing a kill.

One morning we accompany a pack of African wild dogs on the scent of a potential meal. These beautiful and endangered animals are something of a rarity in many parts but here they are quite common. Also known as painted wolves, they are patched black and tan with splashes of white, have large, round upright ears and a fluffy white brush of a tail. Rodney spots them from afar, as usual, and Jaben swings into pursuit so that we are soon racing alongside them, bumping up and down over the rough ground in a thrilling chase, the wind in our hair.

That’s one of the fun things about Sabi Sands – the topography lends itself to stealth and chase. It might not look like the flat, green African plains you’ve seen in National Geographic, with distant snow-capped peaks, but rumbling along a dry riverbed, not knowing what’s around the corner or hiding in the trees above, is exciting.

Soon we notice we’re not the only ones following the dogs, loping hyenas appear, always on the look out for a free lunch. Later we have the privilege of seeing hyena puppies, lying in their own urine but still impishly adorable with their oversized snouts and clumsy paws. But my growing love affair with hyenas is briefly stalled that evening when I hear their laughter for the first time.

We’re treated to a bush dinner, an epic buffet in the middle of nowhere, where the wine flows and the smell of sizzling kudu melts into the night. But as we stand to head back to the lodge, an otherworldly sound rings out which makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up instantly. First a whooping sound, starting low but ending high, reverberates from the shadows, a call apparently as individual as a fingerprint.

As we follow our guide’s torchlight the sounds build in intensity and burst into ominous cackles which seem to echo from every angle. There’s no denying my creeping sense of foreboding – now I understand why these iron-jawed spectres are so dreaded and why they’re associated with witchcraft.

Of course, there is nothing to fear, and it’s actually the next night when I get a real shock. I slope off from the car bonnet bar for a wee while the gin and tonics are being prepared and my boyfriend, acting as lookout, pretends he’s seen a lion when I’m at my most vulnerable (classic move). But we both start when armed guards suddenly appear out of nowhere in the dusk. Wearing military fatigues and carrying some serious weaponry, they look like they mean business. It’s the anti-poaching unit of course, and they do, they’re here to make sure no one gets to the rhino.

On the last day we get to see a rhino in a way I never would have thought possible. The game drive starts as normal. We pass a troop of wildebeest, oversized heads down and grazing, and some graceful zebra in the distance. We finally see two elusive animals, a hippo – just its back, mind – poking out of the last remaining spot of sludge in the dried up lake and a giraffe peering at us through the trees and then picking its way across the bush slowly, purposefully and well away from us. Then one of my favourites, a warthog, closer than ever as it bursts, startled, out of the bush beside us, sprinting away with its spindly tail pointing straight up, the fluffy tip bouncing in the breeze.

Jaben says we’re ready for a bush walk so, fortified with coffee and biscuits, we set off across the sun-baked earth, disturbing a flock of spherical guinea fowl who scatter, heads bobbing in the direction of freedom. We pick our way between termite mounds to keep ourselves in cover but only see animals in the distance, a spiral-antlered kudu, a lone warthog and some buffalo, with their comical horny centre partings.

As we walk I see holes in the ground and, flashing back to the time I spent in Borneo, I ask Jaben what they are, though I think I already know. Spiders. Big hairy tarantulas. “You can feel it biting,” he says, grinning as he pokes a stick down one of the holes.

We pass through a gully in single file and as we come out the other side, Jaben motions for us stop. “We’re going to find the rhino we saw yesterday,” he whispers. We already know that rhino are virtually blind, but is this a good idea? It’s too late to back out if it isn’t. The scrubland doesn’t offer as much cover as we’d like but we keep to it, acutely aware of every twig snapping under our feet. Suddenly, Jaben motions for us to stop. To our left is a thicket of thorny bushes and we spot a glimpse of a grey shape moving.

Jaben tells us to stay still but most of all quiet because they have acute hearing. “You can’t outrun a rhino,” he adds, helpfully. Crouching in the dirt, my heart hammering, I hear our collective ragged breathing – adrenaline, not exertion – along with the irritating buzz of a fly, distant birdsong and the rasp of cicadas. Suddenly he walks into the clearing straight ahead of us. There is no cover in front and at one heart-stopping moment, when he’s only 12 metres away, his delicate ears swivel in our direction.

Every 12 hours a rhino is poached in Africa. Save this amazing animal by funding community-led conaervation and education to stop horn trade in its tracks. savetherhino.org

Magnificently muscular, the white rhino’s pre-historic profile is fearsome but he pads gently, head down, a little bird hopping down his long, squat body. The last we see of him is his tail, an absurdly small appendage for such an imposing beast.

When we leave Sabi Sands I feel as if I’m leaving friends. I swear the group of impala we pass just before the gate are an official leaving party. I will never forget this place or the cast of characters I met.

I still admire hyenas, the sustainability consultants of the bush, making sure nothing goes to waste. I want to be a cat – who doesn’t – but if this was possible I’d need to work towards a fairer division of labour between the sexes. And I love elephants. Is it possible that we can learn more about humanity from these grey giants than from ourselves? We would certainly all do well to listen to nature more.

South Africa is one of many safari destinations, here are some other great wildlife

hot-spots

This elephant haven has unique topography which makes for a series of very different experiences and diverse wildlife. Go on safari by boat, in the vast, green wetlands of the Okavango Delta; stalk black-maned lions in the Kalahari’s grasslands or meerkats in its arid salt pans; or run with the herds in Chobe National Park which has Africa’s largest concentration of game.

If you can’t afford a ticket to space, head to Namibia to search for wildlife in its other-worldly landscapes. The towering, shifting red dunes of Sossusvlei is like a different planet to the grassy plains of Etosha National Park, where you can see flocks of flamingos and the smallest antelope in the world. Then there’s the Skeleton Coast where swirling mists hide colonies of seals.

The Masai Mara is what you imagine when you think ‘safari’ – teeming savannahs and the silhouette of flat-topped acacias against a burnt orange sunset. Here you can get the best seat in the house for nature’s most dramatic event – the great migration – and watch as thousands of wildebeest and other animals thunder past.

This is a feature from Issue 2 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

Fundraising Futures Community Interest Company, Contingent Works, Broadway Buildings,

Elmfield Road, Bromley, Kent,

BR1 1LW. England

Putting our profit to work supporting the work of charitable causes

For the latest travel advice, including security, local laws and passports, visit the Foreign & Commonwealth Office website.

© 2024 All rights reserved

Made with

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELB | session | Associated with Amazon Web Services and created by Elastic Load Balancing, AWSELB cookie is used to manage sticky sessions across production servers. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |

| JSESSIONID | session | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __lc_cid | 2 years | This is an essential cookie for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __lc_cst | 2 years | This cookie is used for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __oauth_redirect_detector | past | This cookie is used to recognize the visitors using live chat at different times inorder to optimize the chat-box functionality. |

| aka_debug | session | Vimeo sets this cookie which is essential for the website to play video functionality. |

| player | 1 year | Vimeo uses this cookie to save the user's preferences when playing embedded videos from Vimeo. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 6 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_164521185_1 | 1 minute | This cookie is set by Google and is used to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description available. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| _hjid | 1 year | This is a Hotjar cookie that is set when the customer first lands on a page using the Hotjar script. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description available. |

| CONSENT | 16 years 3 months 16 days 17 hours 23 minutes | These cookies are set via embedded youtube-videos. They register anonymous statistical data on for example how many times the video is displayed and what settings are used for playback.No sensitive data is collected unless you log in to your google account, in that case your choices are linked with your account, for example if you click “like” on a video. |

| iutk | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is used by Issuu analytic system. The cookies is used to gather information regarding visitor activity on Issuu products. |

| vuid | 2 years | Vimeo installs this cookie to collect tracking information by setting a unique ID to embed videos to the website. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Google DoubleClick IDE cookies are used to store information about how the user uses the website to present them with relevant ads and according to the user profile. |

| mc | 1 year 1 month | Quantserve sets the mc cookie to anonymously track user behaviour on the website. |

| NID | 6 months | NID cookie, set by Google, is used for advertising purposes; to limit the number of times the user sees an ad, to mute unwanted ads, and to measure the effectiveness of ads. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |