Cambodia: Khmer Vert

Cambodia’s tourism industry is still dominated by its cities, old and new, but tourists are now venturing into the Cardamom Mountains to discover its emerging eco-tourism scene, says Lynn Houghton

“…shhhhh. Quiet!” our tour guide hisses through his teeth. “Look ahead. In the trees!” Is it a bird or a snake? Or could it be a wild elephant? In this awe-inspiring wilderness, most of the inhabitants exist only here and nowhere else on earth.

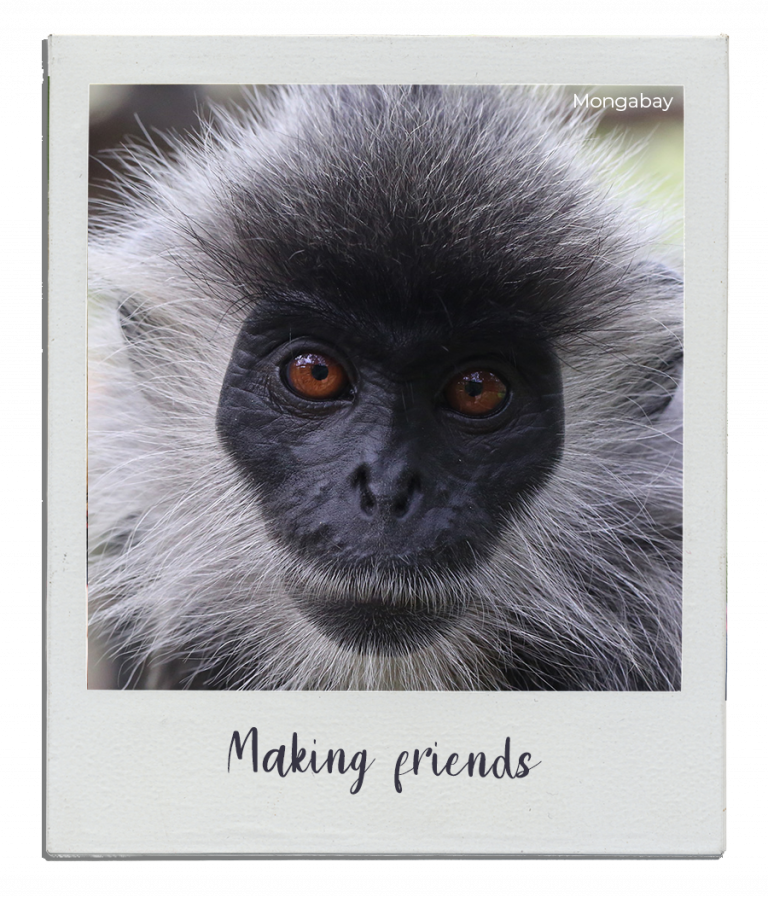

Suddenly, leaves rustle just over the water. The foliage seems to move in tandem like a Mexican wave. Then we spot it: a silver langur launching from one branch to another in a brief but captivating acrobatic display.

From my canoe on the Phipot River in the southern Cardamom Mountains, I am desperately hoping to spy some of this area’s unique creatures.

Temples in the trees

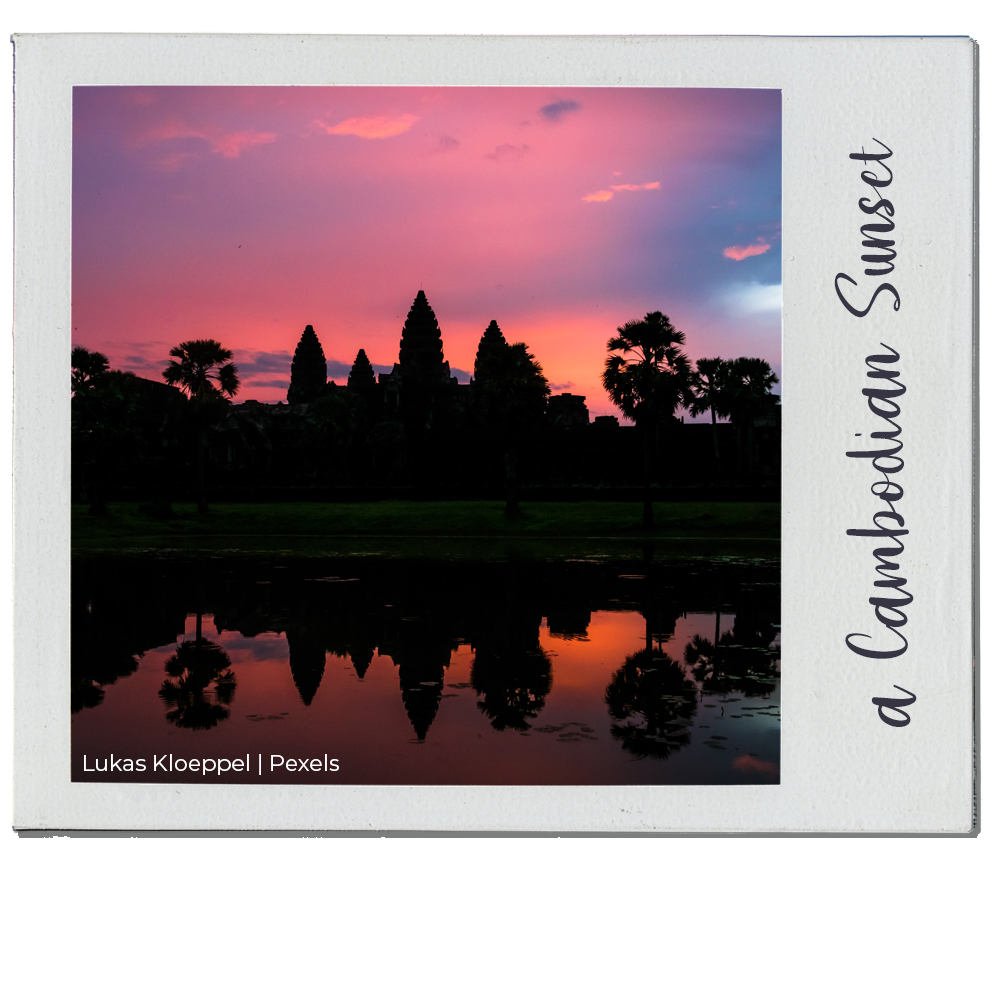

Like everyone in Siem Reap we’re here to see the famous collection of temples, moats and statuary that make up the Angkor complex – including Angkor Wat. The pre-sunrise wake-up call of 4.00am is tortuous but necessary to make the most of this vast area which has a 12km circumference. It also ensures we arrive in time for the morning ‘show’. Taking our seats on a set of stone steps opposite a large moat, we are not disappointed as the sky’s pastel pink hues become coral and then orange and the sun slowly rises behind the iconic outline of Angkor Wat.

This 12th century building was a Hindu mausoleum for a king of the Khmer Empire and later converted to a Buddhist Temple and it forms just one part of the Angkor complex, the remains of the ancient capital which, it is now believed, was the largest pre-industrial city in the world.

Once we cross the bridge and enter the compound, evidence of soldiers’ activity is visible. The bewitching carved stone dancers have been used for target practice and bullet holes still pock their eyes and scatter their torsos. A mere 45 years ago the whole country was controlled by the infamous dictator Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge regime.

Hero Rats

The next morning, we visit a special project dedicated to eradicating landmines, which once blighted the Angkor complex and still dot areas of the country. APOPO is an incredible charity which has a novel solution to these buried war relics, it trains Giant African Pouch Rats to sniff them out safely and quickly.

Across Cambodia there are still unexploded landmines, artillery rounds, grenades, mortars, and even aerial bombs in the rural north. These ugly remnants of three-decade long war have taken a severe toll on the people and Cambodia has the highest landmine accident rate per capita in the world.

At the visitor’s centre in Siem Reap we are briefed by the manager, Mr. Meas Sambat. He emphasises that the animals and their handlers are well protected. A landmine is never triggered by the rats, as they are too light, and they are trained to scratch the ground if they detect one.

The rats are trained by learning to associate the smell of explosive TNT with a tasty treat as well as becoming used to being handled and on a lead. I can see that the animals are extremely attached to their trainers. They work for six years before they retire to a special section of the compound full of stimulating toys and activities.

“We have a remarkable success rate of nearly 93%, with hundreds of hectares of land having been cleared,” Sambat tells us. “Detonating, then removing the landmines and unexploded munitions, mean farmers can replant the rice fields and grow crops such as cashew nuts. It completely changes the lives of rural Cambodian people.”

The big city

The vast numbers of motorcycles darting in and out of every street is like a colony of bees and means the city is always buzzing with phrenetic activity. Old sections of Phnom Penh are connected with chaotic bundles of electrical wire, bringing modern comforts to crumbling buildings.

Our group converges to end the day in luxury at the famous Eclipse roof top bar, where we enjoy cool breezes and spectacular views over a sparkling Phnom Penh.

We head to the outskirts of Phnom Penh the next day, where evidence of the country’s dark past is preserved at the Choeung Ek Genocidal Centre. This is just one of the Khmer Rouge’s infamous ‘killing fields’ where the paranoid communist regime executed thousands of people it believed to be dissenters. It is a sobering experience with visceral memorials of genocide including a monument filled with the skulls of the victims.

It is estimated that between 1.5 and 3 million people died at the hands of the regime – even babies were not spared. Those targeted included the country’s educated, such as teachers and doctors, those with religious beliefs, ethnic minorities and even artists.

For a light end to such a grim day, the last evening is spent at a Cambodian classical dance performance. Slender women wear ornate traditional costumes with tall hats that appear to represent temples, and their stiff poses are accentuated by sinuous hand movements. We also enjoy storytelling and comedy. No doubt the Khmer Rouge would not have allowed any of it.

Cambodia’s past, whether it is the crumbling temples of Angkor Wat or the grim spectre of the Killing Fields, is fascinating. The future of this energetic country could lie in what has been there all along – the jungle. It smothered the temples and eventually spat out the last of the Khmer Rouge and hopefully it will soon usher in a new era of sustainable wealth for the Cambodian people.

This is a feature from Issue 5 of Charitable Traveller. Click to read more from this issue.

by net effect

by net effect